MuseData Encoding Notes

Frances Bennion, whose work is represented here, joined the CCARH staff in 1985, when our encoding and printing systems were still in gestation. She brought a magnificent musical background and a natural inclination towards meticulous detail. Fran had a degree in math, had worked in aeronautical engineering, and was a pianist and cellist. She also raised four musicians (two professional string players and two active amateurs.) At the time she joined us, we were encoding music by J.S. Bach, Handel, Legrenzi, and Corelli. Over the coming years works by Haydn, Mozart, Vivaldi, and other composers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries took places on our agenda.

The original aim was to encode at the Urtext level, meaning complete fidelity to all indications in the source. We remain on that general path today, but over the years, time and practicality have forced us to adopt modern conventions. These include modernization of clef signs, meter signatures, scripts used in text underlay (to avoid replicating Fraktur and the esset in German underlay). In some cases, we may offer condensation of multi-voice works on fewer staves, e.g., two staves in lieu of four for the Bach chorales. It depends on whether the expected purpose is a keyboard transcription or a choral arrangement.

Our surviving digital editions are (a) modernized to conform to current standards of notation, (b) reconciled to the arithmetic of stress and accent in measured music, and (c) follow modern styles of notating duration in passages of notes inégales. Pitch is a more complicated matter. Conventions of marking accidentals varied by country, era, and publisher in earlier centuries. Users are advised to consult the critical notes, which address part-by-part, beat-by-beat issues in underlying sources.

Among our musical data specialists, Fran led the way in turning up ambiguities, discrepancies between sources, and conundrums that were not susceptible to facile solutions. She played a vital role in developing the substantial MuseData holdings. She was a pioneer in transcribing directly from manuscript sources, particularly for Handel operas and oratorios and for the intricacies of Vivaldi concertos. This commentary barely scratches the surface of her methods of her precision, but it gives some idea of the rigor with which she addressed unexpected issues.

Sources

We relied initially on out-of-copyright prints for most of our work (the Bach Gesellschaft edition, Friedrich Chrysander’s edition of Handel, the Augener edition for Corelli et al.). The Eighties ushered in many reprints of part-books for seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Italian prints. By 1987, Fran was encoding directly from seventeenth-century part-books for Corelli trio sonatas. A year or two later, she was working with manuscripts, including some of those with elaborations of Corelli's violin sonatas op. 5. She quickly noticed many cases of divergence from century to century and from source to source. The skills she corralled for these undertakings served well for early prints and manuscripts of works by Handel and Vivaldi. Fran encoded all nine Beethoven symphonies. (In subsequent years, Ed Correia completed all of the Beethoven string quartets and much of the Vivaldi that Fran was not able to complete before her retirement in 2010.)

Matters of interpretation

Beethoven's fifth symphony presented an entirely new problem: the the oboe cadenza at the end of the second movement that forms a bridge to the third movement. In written notation cadenzas do not consume any apparent time, but of course in playing and in sound files cadenzas are rendered in diverse ways by performers. Fran had a quick eye for many problems of interpretation that do not have easy solutions, and it is for this reason we reproduce samples of her “problem” descriptions selectively below. In early music generally there is rarely uniformity of thought on either interpretation of content or presentation in modern editions. Modern performers still like to make their decisions. The thinking that supports any given decision can be highly instructive.

2022 Eleanor Selfridge-Field

Encoding issues

Pitch: Interpretations and editorial interventions

A. Conventions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

The issues listed below are illustrated with short excerpts from Handel’s Concerti grossi op. 6.

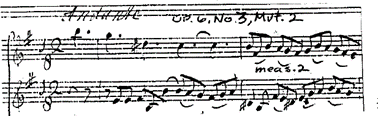

- Accidentals (#, b, n) were restated within the measure, as in measure 2 below. We suppress this convention (as illustrated in Op. 6, No. 2, mvmt 2) and follow modern practice. A controversial change may be mentioned in the critical notes for the work.

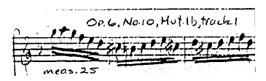

- If an altered note was immediately repeated, the sign would not reiterated in modern notation, but a cautionary one might be required if the pattern continues, as with the C#s in Op. 6, No. 10, mvmt 1b.

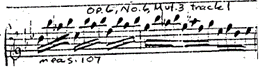

- If an altered note appeared repeatedly in alternation with other notes (e.g. in groups of four sixteenth notes), the sign was not repeated until the harmonic pattern/figure changed (Op. 6, No. 6, mvmt 3).

- If a pitch was altered in an ornamental figure, it had no force beyond its original position.

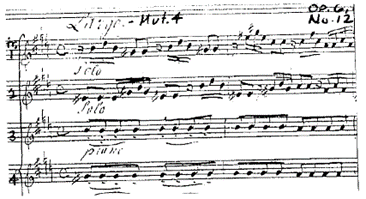

- We occasionally add cautionary signs in elaborate passages with frequent changes in the signage, as above in Op. 6, No. 12, mvmt 4 above.

Encoding note: In our Stage I (pitch/duration) files, the sign * immediately following the duration signifies an editorial accidental. The turning off of an accidental is signed!*

B. Conventions of the 19th century

- If an accidental was tied over a bar-line, the sign was usually omitted in the new bar. We restore the accidental sign in the new bar.

- Page-turns: Nineteenth-century economies often resulted in the absence of repeated clef and key signatures on right-hand page facing one with the same signs. We follow modern practice in including them on every system and every page. Instrument names appear only at the start of each movement, unless there is a change in the nature or number of instruments participating.

C. General conventions

- Ambiguous situations

Editorial conventions of the past have sometimes been applied inconsistently. A particular figure (often a set of four sixteenth notes) may have one altered note in each of several immediately repeated groups. [These inconsistencies also affect dynamics and articulation markings, bowing, slurs, and dotting.] We regularize.

- Contradictions

We run across straightforward contradictions of interpretations between editions. If the situation is unclear or the answer conflicted, we cite individual sources.

Stems and tracks

In older material, stem directions may help to decode voices and intended phrasing, but graphical alignment was not required for polyphonic passages presented within a single staff. We aim for alignment in common with modern usage. Note, though, that in keyboard music graphical conventions can vary widely from modern usage.

- Duration and rhythm

Music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries could involve hemiola (shifted beat) rhythms that temporarily alter the meter. They are indicated in a variety of ways in modern notation. A hemiola often involves two consecutive bars in modern editions.

- Ties

Marks that look like ties to the modern performer’s eye may have been ties, slurs, phrase marks, or even first/second ending indications in earlier material. Conventions surrounding triplets are also widely variant. A “3” over/under a triplet group is common today, but in earlier times they were often omitted. In other cases, the first instance might be marked, but all succeeding groups in the same movement were assumed to be understood to be “simile”. We mark all triplets.