Franz Joseph Haydn: Difference between revisions

| (52 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

===String quartet prints of Haydn's Time=== | ===String quartet prints of Haydn's Time=== | ||

No complete edition of all of Haydn's works was organized until a few decades ago. In the absence of a comprehensive critical edition, Haydn's music has been circulated in a great bevy of short runs from his time to our own. CCARH had the good fortune to acquire bits and pieces of several string-quartet editions from Haydn's lifetime. The concurrent series testify to the popularity of the repertory in general but also to its proliferation in France and England. | No complete edition of all of Haydn's works was organized until a few decades ago. In the absence of a comprehensive critical edition, Haydn's music has been circulated in a great bevy of short runs from his time to our own. CCARH had the good fortune to acquire bits and pieces of several string-quartet editions from Haydn's lifetime. The concurrent series testify to the popularity of the repertory in general but also to its proliferation in France and England. The Hoboken catalog on which we rely today incorporates numbers for some early works that are known today to be spuriously attributed to Haydn. All string quartets and <i>divertimenti</i> begin with the Roman-numberal prefix "III:". | ||

====Music publishers of Haydn's time==== | ====Music publishers of Haydn's time==== | ||

<b> | <b>Robert Bremner</b> (<i>c</i>1713-1789) was a publisher of music in Edinburgh. His main interest was in bringing out primers on how to play specific instruments and mastering techniques such as vibrato.These were occasionally issued together with new issues of string quartets. The collection of plates and copyrights he acquired over his lifetime became an enviable one. | ||

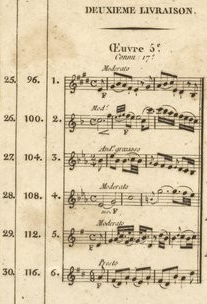

[[File:Pleyel-cat.PNG|thumb|left|1500px|<small>Pleyel's multitiered system of identifying Haydn string quartets. Here we see incipits for the quartets Op. 5, Nos. 1-6, with their through-numbered indications (25-30), and the starting page (<i>Violino primo</i>) of each (96-116) of the "second book".</small>]] | |||

<b>Ignace Joseph Pleyel</b> (1757-1831) was born near Vienna with the name Ignaz Pleyl. Naturalized in France, he pursued a musical education, studying from the age of twelve with Jean-Baptiste Vanhal (1739-1815), then securing support from the count Ladislaus Erdödy to study with Haydn at [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eisenstadt Eisenstadt]. In 1777 Pleyel was named director of music at the court of his benefactor and, soon after, director of the orchestra of Prince Esterhazy at | |||

Eisenstadt. | |||

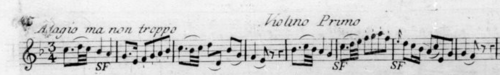

Pleyel's first string quartet appeared in 1782, but two years later he was appointed director of music at the Strasbourg Cathedral. Rising revolutionary sentiments in France in 1791 forced him to go to London, where he joined Haydn in the Salomon concerts. Upon his return to Frence Pleyel was stripped of his position in Strasbourg. Les éditions de la Maison Pleyel began to appear in 1797. They published more than 4,000 chamber works in slightly less than 40 years. In 1802 the Maison published a complete edition of Haydn string quartets in performing parts. Dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte, it is fully reproduced [https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/10551832 here]. In 1807 the first Pleyel pianos began to appear. Ultimately popularity of Pleyel pianos eclipsed the importance of its Haydn (and other) prints. The small score edition of the quartets of Haydn's popular "Op. 20" reproduced here must come from the period 1815-1830. Pleyel was also involved in the distribution of Haydn symphonies in miniature editions. | |||

[[File:Q1-m2_1802.PNG|thumb|right|500px|<small>Snippet from the second movement of Haydn's Quartet No. 1 (Pleyel, 1802). Stanford University Libraries. Used by permission.</small>]] | |||

<b>Pleyel's numbering systems </b> were multiple. He provided a straight-through numbering (Nos. 1-74), a sectionalized series of <i>livraisons</i> termed <i>oeuvres</i> (Nos. 1-14), and work numbers (starting from 1) within each <i>oeuvre</i>. The passage of Haydn's works through other hands resulted in several variations on the original models. The [https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b530592620/f9.item thematic index] in the 1802 print helps to clarify various numbering systems. | |||

<b>Charles Simon Richault</b> (1780-1866) of Chartres became an apprentice in music printing to [https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C3%A9r%C3%B4me-Joseph_de_Momigny Jérome-Joseph de Momigny] (1762-1842), whose primary interest was in formal theories of music. Richault's independent activity as a music publisher started in 1805. After Pleyel's death in 1834, several publishers bid on various components of his recently compiled catalog of several thousand works. The Richault works linked here were among those that came directly from the Pleyel 1834 catalog but did not reiterate plate numbers. The Richault firm became much better known in later decades later, when it was operated by the founder's grandson Léon. Under his management Les édition Richault became known for first editions of Berlioz, the first French editions of Bach and Handel oratorios, and the more standard repertories of Beethoven symphonies and Mozart concertos. | |||

<b>The Trautwein</b> firm operated as a book and music distributor in Berlin from 1829 until the firm was taken over in 1890. Its music offerings included dances, songs, piano, and chamber music. Haydn's quartets may have been the earliest repertory in its catalog. Among the publishers listed here it was the most recent in origin. What it gained from that position was a consistency that is sometimes lacking in earlier exemplars. The quartets reproduced here appeared in 1840 and were identified inside each print as coming from a "Leipzig cahier". | |||

===Haydn quartets: Table of reproductions from early prints=== | |||

{{Template:HaydnQuartets}} | {{Template:HaydnQuartets}} | ||

The identification of works in these scans requires consultation of the finding chart linked above. The lack of a comprehensive edition parallels the absence of a comprehensive catalog of Haydn's music, although this need was substantially met | The identification of works in these scans requires consultation of the finding chart linked above. The lack of a comprehensive edition parallels the absence of a comprehensive catalog of Haydn's music, although this need was substantially met by the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoboken_catalogue catalog] of Anthony van Hoboken. | ||

Musicians who leaf through the Haydn quartet scans rapidly develop insights in the condition of music circulation in Haydn's time. It is immediately noticeable that during the intervening two centuries many conventions of notation, particularly regardings turns and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grace_note grace notes], have changed. | Musicians who leaf through the Haydn quartet scans rapidly develop insights in the condition of music circulation in Haydn's time. It is immediately noticeable that during the intervening two centuries many conventions of notation, particularly regardings turns and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grace_note grace notes], have changed. | ||

A much larger proportion of melodic notes were conveyed through | A much larger proportion of melodic notes were conveyed through grace notes than would be the case today. (George Barth's 1991 article on Mozart performance gives some sense of this situation.) The technically astute will find, if they investigate our encoded score data, these editions do not serve modern editors at all well. Beat-regularization squeezes many of those same small notes out of the file, which regulates musical flow by bar structure, and extensive annotation is needed to convey the composer's intentions. | ||

===Piano sonatas printed in <i>c</i>1900=== | ===Piano sonatas printed in <i>c</i>1900=== | ||

| Line 47: | Line 57: | ||

Quartet numbers which are commonly used in modern performing editions and recordings reflect the arbitrary assignment of opus numbers as used by more recent publishers. Each publisher had his own self-referential system of identifying new titles. As many of six or several instances of a fictitious String Quartet Op. 1 could prove to be musically independent works. | Quartet numbers which are commonly used in modern performing editions and recordings reflect the arbitrary assignment of opus numbers as used by more recent publishers. Each publisher had his own self-referential system of identifying new titles. As many of six or several instances of a fictitious String Quartet Op. 1 could prove to be musically independent works. | ||

When quartets were published in sets, the order of works within the set was determined by the publisher. It did not necessarily duplicate the order used by another publisher. The order in which the works were arranged varied from one collection to the next. | [[File:PleyelOp20a.png|300px|thumb|left|<small>Thematic index as given in the <i>Violino primo</i> part of the six quartets of "Op. 20" as published by Pleyel in 1802 (Stanford University Libraries). </small>]] | ||

When quartets were published in sets, the order of works within the set was determined by the publisher. It did not necessarily duplicate the order used by another publisher. The order in which the works were arranged varied from one collection to the next. Widely circulated editions of the past half-century employ their own naming and numbering systems. Musicians can get some sense of this from the thematic index included with the Pleyel editions of string parts published in 1802. In the Violino Primo part, the listings for the six quartets of Op. 20 (1802 print) appear as in the image here. | |||

An encoded version of Haydn's Op. 20, n. 5 in F Minor, was recently synchronized with a performance by the St. Lawrence String Quartet to enable users to follow a scrolling score. The individual movements of the video are here: | |||

* I. [https://www.ccarh.org/haydn/op20n5/mvmt1v Moderato] | |||

* II. [https://www.ccarh.org/haydn/op20n5/mvmt2v Menuet] | |||

* III. [https://www.ccarh.org/haydn/op20n5/mvmt3v Adagio] | |||

* IV. [https://www.ccarh.org/haydn/op20n5/mvmt4v Finale] | |||

The quartet has many unusual features. Among them are the placement of a minuet as a second movement, the warm Adagio (closely resembling the aria "Cara, nel dirti addio" in Benedetto Marcello's cantata "Qual mai fatto inumano", noted for its two-octave range), and the double fugue of the Finale. The performers [L-R) in the videos are [http://www.slsq.com/geoff-nuttall Geoff Nuttall], [http://owendalby.com/ Owen Dalby], [https://costanzacello.com/about Christopher Costanza], and [https://music.stanford.edu/people/lesley-robertson Lesley Robertson]. The videos form part of Stephen Hinton's online course on [https://online.stanford.edu/courses/sohs-ymusicstrnqrtet-defining-string-quartet-haydn Haydn quartets] offered through Stanford Continuing Studies. | |||

==Symphonic editions (CCARH)== | ==Symphonic editions (CCARH)== | ||

| Line 64: | Line 85: | ||

* George Barth, "Mozart performance in the nineteenth-century," <i>Early Music</i>, 19/4 (Nov. 1991), 538-552. | * George Barth, "Mozart performance in the nineteenth-century," <i>Early Music</i>, 19/4 (Nov. 1991), 538-552. | ||

* Rita Benton, "Pleyel as a music publisher," <i>Journal of the American Musicological Society</i>, 32/1 (1979), 125-140. | |||

==Link== | |||

Shortcut to this page: https://haydn.ccarh.org | |||

Latest revision as of 00:25, 13 April 2025

Franz Josef Haydn was one of the best-loved composers of the eighteenth century. His string quartets, symphonies, concertos, masses, keyboard, and chamber music all became models of their genres. Haydn encapsulated the eighteenth-century ideal of well articulated organization, balance of resources with enough rotation to avoid blandness, and a critical ear. The music was famously good-natured and found an easy reception.

Yet Haydn himself never received the praise for his operas he would have wished. Many were written for performance in Eisenstadt, where his employer's wife was an Italian noblewoman with a significant interest in the genre. Ironically, Haydn's operas are more approachable today than they were in his time. Some, on texts by Carlo Goldoni, are comic. Many contain a pleasant balance between vocal and instrumental pieces, for Haydn was even-handed in his approach to all kinds of music.

Facsimiles

String quartet prints of Haydn's Time

No complete edition of all of Haydn's works was organized until a few decades ago. In the absence of a comprehensive critical edition, Haydn's music has been circulated in a great bevy of short runs from his time to our own. CCARH had the good fortune to acquire bits and pieces of several string-quartet editions from Haydn's lifetime. The concurrent series testify to the popularity of the repertory in general but also to its proliferation in France and England. The Hoboken catalog on which we rely today incorporates numbers for some early works that are known today to be spuriously attributed to Haydn. All string quartets and divertimenti begin with the Roman-numberal prefix "III:".

Music publishers of Haydn's time

Robert Bremner (c1713-1789) was a publisher of music in Edinburgh. His main interest was in bringing out primers on how to play specific instruments and mastering techniques such as vibrato.These were occasionally issued together with new issues of string quartets. The collection of plates and copyrights he acquired over his lifetime became an enviable one.

Ignace Joseph Pleyel (1757-1831) was born near Vienna with the name Ignaz Pleyl. Naturalized in France, he pursued a musical education, studying from the age of twelve with Jean-Baptiste Vanhal (1739-1815), then securing support from the count Ladislaus Erdödy to study with Haydn at Eisenstadt. In 1777 Pleyel was named director of music at the court of his benefactor and, soon after, director of the orchestra of Prince Esterhazy at Eisenstadt. Pleyel's first string quartet appeared in 1782, but two years later he was appointed director of music at the Strasbourg Cathedral. Rising revolutionary sentiments in France in 1791 forced him to go to London, where he joined Haydn in the Salomon concerts. Upon his return to Frence Pleyel was stripped of his position in Strasbourg. Les éditions de la Maison Pleyel began to appear in 1797. They published more than 4,000 chamber works in slightly less than 40 years. In 1802 the Maison published a complete edition of Haydn string quartets in performing parts. Dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte, it is fully reproduced here. In 1807 the first Pleyel pianos began to appear. Ultimately popularity of Pleyel pianos eclipsed the importance of its Haydn (and other) prints. The small score edition of the quartets of Haydn's popular "Op. 20" reproduced here must come from the period 1815-1830. Pleyel was also involved in the distribution of Haydn symphonies in miniature editions.

Pleyel's numbering systems were multiple. He provided a straight-through numbering (Nos. 1-74), a sectionalized series of livraisons termed oeuvres (Nos. 1-14), and work numbers (starting from 1) within each oeuvre. The passage of Haydn's works through other hands resulted in several variations on the original models. The thematic index in the 1802 print helps to clarify various numbering systems.

Charles Simon Richault (1780-1866) of Chartres became an apprentice in music printing to Jérome-Joseph de Momigny (1762-1842), whose primary interest was in formal theories of music. Richault's independent activity as a music publisher started in 1805. After Pleyel's death in 1834, several publishers bid on various components of his recently compiled catalog of several thousand works. The Richault works linked here were among those that came directly from the Pleyel 1834 catalog but did not reiterate plate numbers. The Richault firm became much better known in later decades later, when it was operated by the founder's grandson Léon. Under his management Les édition Richault became known for first editions of Berlioz, the first French editions of Bach and Handel oratorios, and the more standard repertories of Beethoven symphonies and Mozart concertos.

The Trautwein firm operated as a book and music distributor in Berlin from 1829 until the firm was taken over in 1890. Its music offerings included dances, songs, piano, and chamber music. Haydn's quartets may have been the earliest repertory in its catalog. Among the publishers listed here it was the most recent in origin. What it gained from that position was a consistency that is sometimes lacking in earlier exemplars. The quartets reproduced here appeared in 1840 and were identified inside each print as coming from a "Leipzig cahier".

Haydn quartets: Table of reproductions from early prints

| Hoboken no. | Title (genre) | Bremner work nos. | Trautwein plate nos. | Pleyel | Richault | RISM A/I print index | Work | Opus | Comments, corollaries

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| III:1 | Divertimento | Op. 1, n.1 | H 3437 | 1 | Op. 1, n.1 | “The Hunt” | |||

| III:2 | Divertimento | Op. 1, n.2 | H 3437 | 2 | Op. 1, n.2 | ||||

| III:3 | Divertimento | Op. 1, n.3 | H 3437 | 3 | Op. 1, n.3 | ||||

| III:4 | Divertimento | Op. 1, n.4 | H 3437 | 4 | Op. 1, n.4 | ||||

| III:5 | Divertimento | Op. 1, n.5 | H 3437 | 5 | Op. 1, n.5 | spurious | |||

| III:6 | Divertimento | Op. 1, n.6 | H 3437 | 6 | Op. 1, n.6 | ||||

| III:7 | Divertimento | 7 | Op. 2, n.1 | no copy | |||||

| III:8 | Divertimento | 8 | Op. 2, n.2 | no copy | |||||

| III:9 | Divertimento | Op. 2, n.3 | spurious | ||||||

| III:10 | Divertimento | 9 | Op. 2, n.4 | no copy | |||||

| III:11 | Divertimento | Op. 2, n.5 | spurious | ||||||

| III:12 | Divertimento | 10 | Op. 2, n.6 | no copy | |||||

| III:13 | String quartet | Op. 3, n.1 | spurious | ||||||

| III:14 | String quartet | Op. 3, n.2 | spurious | ||||||

| III:15 | String quartet | Op. 3, n.3 | spurious | ||||||

| III:16 | String quartet | Op. 3, n.4 | spurious | ||||||

| III:17 | String quartet | Op. 3, n.5 | spurious | ||||||

| III:18 | String quartet | Op. 3, n.6 | spurious | ||||||

| III:19 | Divertimento | 12 | Op. 9, n.1 | no copy | |||||

| III:20 | Divertimento | 704 | 14 | Op. 9, n.2 | |||||

| III:21 | Divertimento | 800 | 13 | Op. 9, n.3 | |||||

| III:22 | Divertimento | 11 | Op. 9, n.4 | no copy | |||||

| III:23 | Divertimento | 15 | Op. 9, n.5 | no copy | |||||

| III:24 | Divertimento | 16 | Op. 9, n. | no copy | |||||

| III:25 | Divertimento | 705 | 18 | Op. 17, n.1 | |||||

| III:26 | Divertimento | 724 | 17 | Op. 17, n.2 | |||||

| III:27 | Divertimento | 777 | 21 | Op. 17, n.3 | |||||

| III:28 | Divertimento | 19 | Op. 17, n.4 | no copy | |||||

| III:29 | Divertimento | 811 | 22 | Op. 17, n.5 | |||||

| III:30 | Divertimento | 834 | 20 | Op. 17, n.6 | |||||

| III:31 | Divertimento | 752 | IV/1 [1] | 28 | Op. 20, n.1 | ||||

| III:32 | Divertimento | 799 | 25 | Op. 20, n.2 | |||||

| III:33 | Divertimento | 26 | Op. 20, n.3 | no copy | |||||

| III:34 | String quartet | 815 | IV/2 | H 3363 | 27 | Op. 20, n.4 | |||

| III:35 | String quartet | 698 | IV/1 | H 3363 | 23 | Op. 20, n.5 | |||

| III:36 | String quartet | IV/3 | H 3363 | 24 | Op. 20, n.6 | ||||

| III:37 | String quartet | 761 | VII/1 | H 3364 | 31 | Op. 33, n.1 | Op. 33, nn. 1-6.

] | ||

| III:38 | String quartet | 699 | VII/2 | H 3364 | 30 | Op. 33, n.2 | |||

| III:39 | String quartet | VII/3 | H 3364 | 32 | Op. 33, n.3 | ||||

| III:40 | String quartet | 812 | VIII/1 | H 3364 | 34 | Op. 33, n.4 | |||

| III:41 | String quartet | 700 | VIII/2 | H 3364 | 29 | Op. 33, n.5 | |||

| III:42 | String quartet | VIII/3 | H 3364 | 33 | Op. 33, n.6 | ||||

| III:43 | String quartet | 835 | 35 | Op. 42 | |||||

| III:44 | String quartet | VI/3 | H 3366 | 36 | Op. 50, n.1 | ||||

| III:45 | String quartet | 805 | VI/2 | H 3366 | 37 | Op. 50, n.2 | |||

| III:46 | String quartet | 759 | VI/3 | H 3366 | 38 | Op. 50, n.3 | |||

| III:47 | String quartet | 706 | VI/2 | H 3366 | 39 | Op. 50, n.4 | |||

| III:48 | String quartet | 781 | V/1 | H 3366 | 40 | Op. 50, n.5 | |||

| III:49 | String quartet | 810 | VI/1 | H 3366 | 41 | Op. 50, n.6 | |||

| III:50 | Arr. of Die sieben letzten Worte | ||||||||

| III:51 | Arr. of Die sieben letzten Worte | ||||||||

| III:52 | Arr. of Die sieben letzten Worte | ||||||||

| III:53 | Arr. of Die sieben letzten Worte | ||||||||

| III:54 | Arr. of Die sieben letzten Worte | ||||||||

| III:55 | Arr. of Die sieben letzten Worte | ||||||||

| III:56 | Arr. of Die sieben letzten Worte | ||||||||

| III:57 | String quartet | 771 | 42 | Op. 54, n.2 | no copy | ||||

| III:58 | String quartet | 735 | 43 | Op. 54, n.1 | |||||

| III:59 | String quartet | 814 | 44 | Op. 54, n.3 | |||||

| III:60 | String quartet | 779 | 45 | Op. 55, n.1 | |||||

| III:61 | String quartet | 46 | Op. 55, n.2 | no copy | |||||

| III:62 | String quartet | 803 | 47 | Op. 55, n.3 | |||||

| III:63 | String quartet | 697 | 53 | Op. 64, n.5 | |||||

| III:64 | String quartet | 784 | 52 | Op. 64, n.6 | |||||

| III:65 | String quartet | 783 | 48 | Op. 64, n.1 | |||||

| III:66 | String quartet | 746 | 51 | Op. 64, n.4 | |||||

| III:67 | String quartet | 798 | 50 | Op. 64, n.3 | |||||

| III:68 | String quartet | 760 | 49 | Op. 64, n.2 | |||||

| III:69 | String quartet | 711 | IX/1 | H 3372 | 54 | Op. 71, n.1 | |||

| III:70 | String quartet | 749 | IX/2 | H 3372 | 55 | Op. 71, n.2 | |||

| III:71 | String quartet | 782 | IX/3 | H 3372 | 56 | Op. 71, n.3 | |||

| III:72 | String quartet | 745 | X/1 | 57 | Op. 74, n.1 | ||||

| III:73 | String quartet | 709 | X/2 | 58 | Op. 74, n.2 | ||||

| III:74 | String quartet | 785 | X/3 | 59 | Op. 74, n.3 | ||||

| III:75 | String quartet | 751 | I/1 | 60 | Op. 76, n.1 | ||||

| III:76 | String quartet | 808 | I/2 | 61 | Op. 76, n.2 | ||||

| III:77 | String quartet | 695 | I/3 | 62 | Op. 76, n.3 | ||||

| III:78 | String quartet | 754 | II/1 | 63 | Op. 76, n.4 | ||||

| III:79 | String quartet | 707 | II/2 | 64 | Op. 76, n.5 | ||||

| III:80 | String quartet | 801 | II/3 | 65 | Op. 76, n.6 | ||||

| III:81 | String quartet | 703 | 66 | Op. 77, n.1 | |||||

| III:82 | String quartet | 727 | 67 | Op. 77, n.2 | |||||

| III:83 | String quartet | 68 | Op. 103 | unfinished |

The identification of works in these scans requires consultation of the finding chart linked above. The lack of a comprehensive edition parallels the absence of a comprehensive catalog of Haydn's music, although this need was substantially met by the catalog of Anthony van Hoboken.

Musicians who leaf through the Haydn quartet scans rapidly develop insights in the condition of music circulation in Haydn's time. It is immediately noticeable that during the intervening two centuries many conventions of notation, particularly regardings turns and grace notes, have changed.

A much larger proportion of melodic notes were conveyed through grace notes than would be the case today. (George Barth's 1991 article on Mozart performance gives some sense of this situation.) The technically astute will find, if they investigate our encoded score data, these editions do not serve modern editors at all well. Beat-regularization squeezes many of those same small notes out of the file, which regulates musical flow by bar structure, and extensive annotation is needed to convey the composer's intentions.

Piano sonatas printed in c1900

Chamber music: Digitized sources

A recent online exhibit of Haydn resources at Stanford University provides a useful overview of the varied genres in which the composer worked. Some of the fragmentation in Haydn's oeuvre owed to the vicissitudes of patronage. Only recently a composer might have been supported throughout his life by a duke or prince. Haydn's fortunes were mixed. A great deal of his music is associated with the Esterhazy family, who had one court in Eisenstadt (on the Austrian side of today's border with Hungary) and another, grander one, some miles east of the border. Like most Austro-Hungarian, Bohemian, and Moravian nobles of the time, the Esterhazy princes also had a town house in Vienna. Chamber music found a place both in habitual locales and in Vienna.

String quartets

Haydn contributed generously to the chamber music repertory. He is most strongly associated today with the string quartet, a genre in which he coached followers including Mozart and Beethoven. The quartet genre was not so distinct then from closely associated string works, such as the divertimento and the sinfonia concertante, as it later became.

CCARH conducted experiments in encoding from early editions in the 1990s. The Haydn quartet repertory offered a particularly thorny array of available materials with no coordination between them. We offer facsimiles of the editions and some encodes files without any warranty. The notational style of early editions is often ill-suited to encoding. The variability between publishers was considerable. Current users would want to re-edit the data before using it. Yet for those studying the difficulties of the task, we have posted these materials without any restrictions on their use.

Catalog numeration systems

Three systems of numeration for Haydn quartets are in common use. One enumerates single works, one enumerates collections of works by “opus number,” and one (“Hoboken”) assigns an arbitrary number to single works for bibliographical reference. This listing is ordered by the first, with cross-references to the other two. In efforts to encode the early prints, we encountered basic problems of reference: Which exact work was under discussion? This led is to create a table to coordinate all the materials. It is instructive in clarifying the scope of the problem. <Add table>

A Hoboken catalog designation contains a Roman numeral prefix (III=the string quartet category) and an Arabic numeral indicating the approximate order in which the work was composed (or assumed to be composed), e.g. III:10. (Some numbered works are now known to be spurious and should be excluded from analytical applications.)

Early and recent editions of Haydn string quartets

Most Haydn quartets in the MuseData database come from early nineteenth-century editions, especially those by Trautwein, Pleyel, and Bremmer. Most Haydn quartets were published in small groups of works, so one print number may pertain to several works.

Quartet numbers which are commonly used in modern performing editions and recordings reflect the arbitrary assignment of opus numbers as used by more recent publishers. Each publisher had his own self-referential system of identifying new titles. As many of six or several instances of a fictitious String Quartet Op. 1 could prove to be musically independent works.

When quartets were published in sets, the order of works within the set was determined by the publisher. It did not necessarily duplicate the order used by another publisher. The order in which the works were arranged varied from one collection to the next. Widely circulated editions of the past half-century employ their own naming and numbering systems. Musicians can get some sense of this from the thematic index included with the Pleyel editions of string parts published in 1802. In the Violino Primo part, the listings for the six quartets of Op. 20 (1802 print) appear as in the image here.

An encoded version of Haydn's Op. 20, n. 5 in F Minor, was recently synchronized with a performance by the St. Lawrence String Quartet to enable users to follow a scrolling score. The individual movements of the video are here:

The quartet has many unusual features. Among them are the placement of a minuet as a second movement, the warm Adagio (closely resembling the aria "Cara, nel dirti addio" in Benedetto Marcello's cantata "Qual mai fatto inumano", noted for its two-octave range), and the double fugue of the Finale. The performers [L-R) in the videos are Geoff Nuttall, Owen Dalby, Christopher Costanza, and Lesley Robertson. The videos form part of Stephen Hinton's online course on Haydn quartets offered through Stanford Continuing Studies.

Symphonic editions (CCARH)

Unlike other major composers of his generation, Haydn was not honored with a catalogue or a complete edition of works in the nineteenth century. The reasons for this are many and varied. Haydn's chamber music was printed in short editions by scattered publishers, each with a different system for numbering both works and editions. The Hoboken catalogue does its job well but it often difficult to link up with random editions. (See further remarks under String Quartets. Comprehensive Haydn symphony lists appear in the Hoboken Thematic Catalogue.

The London Symphonies

By 1790, Haydn had spent three decades in the employ of the Esterhazy princes. The death of Prince Nicholas led inadvertently the dismissal of the court orchestra. A new offer of patronage from the German impresario J. P. Salomon enabled Haydn to hear his music played by an orchestra of substantial size in London. Haydn's music was already well known and frequently heard there. An added benefit to Haydn was the local publishers were eager to bring out the latest works and to license further editions on the Continent. He ultimately prepared to two sets of six symphonies, one set performed in 1791-92 and the other in 1794-95. Apart from their great success in London, many of these works have remained favorites every since.

Our selection of encoded symphonies emphasizes the later works that show off his talents to best advantage. Users will find that each one is different from the others but fully transparent.

| Symphony No. (Date) | Hoboken No. | Genre / Instruments | Key | Nickname | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. 93 (1791) | I:093 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | D Major | Full score | |

| No. 94 (1791) | I:094 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | G Major | "The Surprise" | Full score |

| No. 95 (1791) | I:095 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | C Minor | Full score | |

| No. 96 (1791) | I:096 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | D Major | "The Miracle" | Full score |

| No. 97 (1791-92) | I:097 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | C Major | Full score | |

| No. 98 (1791-92) | I:098 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | B♭ Major | Full score | |

| No. 99 (1793) | I:099 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Cl/B♭, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | E♭ Major | Full score | |

| No. 100 (1793-94) | I:100 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | G Major | "The Military" | Full score |

| No. 101 (1793-94) | I:101 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Cl/A, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | D Major | "The Clock" | Full score |

| No. 102 (1794) | I:102 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | B♭ Major | Full score | |

| No. 103 (1795) | I:103 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Cl/B♭ 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | E♭ Major | "The Drumroll" | Full score |

| No. 104 (1795) | I:104 | Symphony / 2Fl, 2Ob, 2Cl/A, 2Bn; 2Hrn/D, 2Tr/D, Tmp; 2V, Va, Vc, Cb | D Major | "London" | Full score |

Bibliography

- George Barth, "Mozart performance in the nineteenth-century," Early Music, 19/4 (Nov. 1991), 538-552.

- Rita Benton, "Pleyel as a music publisher," Journal of the American Musicological Society, 32/1 (1979), 125-140.

Link

Shortcut to this page: https://haydn.ccarh.org