Juditha triumphans

Contents

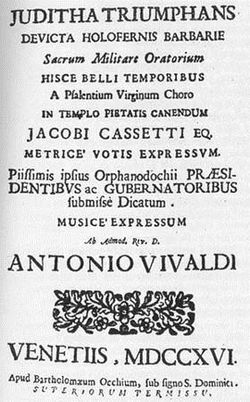

Juditha triumphans

More than any of his other works, Vivaldi's only surviving oratorio, Juditha triumphans, was single-mindedly focused on promoting the image of the Venetian Republic in a military alliance involving Austria and the Papacy. In synchrony with the launch of several new warships and a major battle for the defense of the Adriatic island of Corfù, the importance of Juditha triumphans rested entirely on an analogy. The Bethulian widow Judith represents the Venice Republic, her nemisis Holofernes the Ottomans. At the time the Ottoman army was menacing parts of the Austro-Hungarian empire on land and the Venice dwindling maritime Republic on the Adriatic.

One is aware from the first few notes that this is a staunchly militaristic work: the trumpets greet us almost brazenly, the chorus reminds us at intervals that this is a work with the purpose, and it all ends as militantly as it began. Yet Juditha triumphans is full of tender, affective writing. Abra is a fictional "nurse" who demurely follows the widowed Bethulian queen Judith on her murderous mission. Vivaldi heightens attention the work's most significant moments through the use of a series of changing instrumental obbligati. In the architecture of the whole, instrumental color plays a significant role in delineating changes of mood and also in symbolizing diverse universal conceptions--the passage of time (theorboes), fidelity (the oboe), rusticity (the recorder), and so forth.

Giacomo Cassetti derived the tale from the Apocrypha. He specified its genre as a "sacred military oratorio." The seriousness of its intention was reinforced through its dedication to Johann Matthias (1661-1747), count of Schulenburg, the marshal of the forces designated to defend Corfù, the Republic's last stronghold of its diminishing maritime empire.

Historical Background

The motivation for Juditha triumphans—with regard to both its substance and its timing—was inseparable with the political agenda of the Venetian Republic which, in league with the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire, was engaged in an all-out effort to turn back the advances of the Ottomans in and near the Balkans. The Venetians had lost the island of Crete at the end of the 21-year-long War of Candia (Heraclion) in 1669.

The Venetians concentrated all their naval defenses on the island of Corfù (which they had held since 1396) in 1715 and prepared for a rigorous defense. The Venetian Arsenal prepared several new galleys. Schulenburg recruited several tens of thousands of troops. The fleet sailed early in February 1716.

The defense of Corfù peaked between July 25 and August 20, 1716. Venice prevailed. The crews drifted back to the lagoon in November. Upon their arrival they were required to spend a month in quarantine, from which they emerged at staggered points throughout December. Schulenburg himself was freed on the third day of January 1717, a Sunday. This is the likely date for the performance of Juditha triumphans. The Venetians probably anticipated an Advent performance when the libretto was published, but since the civic year was not advanced until March 1, our dating of January 3, 1717 fell within their year 1716.

The Oratorio of Vivaldi's Time

Juditha is the only oratorio by Vivaldi that survives, but written evidence documents a long history for the genre in Venice's four orphanage-conservatories (ospedali). Francesco Gasparini (1668-1727), Vivaldi's first superior there, was among the oratorio composers, as were Carlo Francesco Pollarolo (c. 1653-1723) at the Incurabili, and the slightly earlier figures Giovanni Legrenzi (1626-1690) and Carlo Pallavicino (c. 1630-1688), who served respectively at the Mendicanti and Ospedaletto. It was the usual practice of the Venetian ospedali to present oratorios on the Sunday afternoons of Advent and Lent (the penitential seasons preceding Christmas and Easter).

Oratorios given in the ospedali were sung in Latin, although in most other institutions throughout Italy they were sung in the vernacular language. Among settings of the same story the Giuditta of Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725), composed in 1693 or 1694 for the robust resources of Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni (1667-1740 for performance in Rome’s Palazzo della Cancelleria is particularly noted.

Among oratorios survived only by anonymous texts, a shorter, simpler La Giuditta was given in 1713 at the no longer extant church of San Leonardo, Padua, in 1713 under the auspices of Laura d'Este, a member of the congregation of the Santissima Annonziata. This Giuditta had roles only for Judith, Ozias, Holofernes, and his unnamed captain. Holofernes dominanted the work, opening it with a vehement denunciation of Jews. Judith sang only twice. It was not, therefore, a work of the same ambitions as Vivaldi's, nor did it have any immediate pertinence to political affairs. Giacomo Cassetti, the librettist of the Vivaldi work, had at least two other oratorios to his credit. Both were given Padua (1702, 1708). They too were less ambitious works than this one.

The Text of Juditha triumphans

Casetti's text can be read either as the script for a pep rally or as a symbolic re-enactment of Venetian triumph over Ottoman troops. Their leader Holofernes is an adversary Judith vanquishes by seduction. She first lures him to her tent, then withstands his advances long enough to ply him with drink (early in Part Two of the oratorio), and then beheads him (an event that was the subject of countless depictions in the arts of the time). Christianity prevails, fulfilling the main objective of the work, but sustains its militancy even in victory.

In such a simplistic account the characters of Judith and Holofernes are easily contrasted. The righteous widow Judith is intent on defending the Faith (i.e., Venice), and her arias define her as forthright and determined. Music of sympathy and quiet persuasion falls to Abra. By turns we find Holofernes, the Ottoman aggressor, to be angry, seductive, drunk, and betrayed. The head priest Ozias and the head eunuch Vagaus serve their masters in conventional but musically persuasive ways.

Few works by Vivaldi exhibit such a close coupling of political motive, text, and music. His imitations of Janissary bands permeate the surface, but at a deeper level most of the woodwinds serve to underscore a fleeting sentiment or turn of events.

Listener's Guide to Juditha triumphans

Part One

All of the unusual instruments play a symbolic role in the soundscape of the overall narrative. Vivaldi cycles through them as the story unfolds. Juditha begins and ends with substantial choruses but was not provided with an opening sinfonia. This seems to have been intentional: Vivaldi wanted to get to action immediately. Holofernes opens the dialogue with his aria "Nil arma, nil bella" ("No arms, no war"). Each character in turn is introduced. The Assyrian soldiers’ chorus “O quam vaga” (“How beautiful…”) signals the initiation of a plan of action. It emphasizes dissonant intervals that were associated at the time with the Middle East. The descending tetrachord in the bass had long been emblematic of travail.

Judith plots her strategy in “Quanto magis generosa” (“How generous…”), an aria in the unusual key of Eb Major. Its obbligato for viola d’amore, a bowed instrument with six regular and six sympathetic strings. The ethereal response they produced was suggestive of emotional twittering. They move Holofernes enough for him to take Judith’s bait, as he sings lovingly in “Sede, o cara” (“Come sit, my beloved”).

Vagaus summons his Assyrian troops in the aria “O servi volate” (“O servants, be quick”). The restriction of the accompaniment to theorboes and harpsichords produces a crisp, thin sounds, but the steady rhythm and its rapid tempo simulate hurrying. Judith calls Abra to her side in the aria “Veni, veni mi sequere fide” (“Come, come follow me”), which in order to imitate a turtledove offers a chalumeau (shawm) obbligato.

Part Two

As the second part of the oratorio begins Ozias scans the heavens in the aria “O sidera, o stellae” (“O stars, o stars”). Vivaldi provides “shooting star” figures in the string section. Holofernes observes the darkness and notes that he is surrounded by shadows (“Nox obscura tenebrosa”). Judith reflects in response on the rapid passage of time (“Transit aetas”). Here that transit is simulated by the plucking of the mandolin and the pizzicato violins.

Holofernes declares his love for Judith (“Noli, o cara, te adorantis”), but alert listeners will notice the aria’s accompaniment by oboe and organ. The oboe often signaled death, while the organ had ushered lost souls into the Underworld in Renaissance performances of tragedies. Holofernes' demise is implied, as if in a Greek tragedy, by the chorus that sings “Plena nectare non mero” (“Full of pure nectar”). Vivaldi introduces two chalumeaux to underscore the now subdued Turkish threat.

After beheading Holofernes, Judith is able to declare Peace (“Vivat in pace, et pax regnet sincera”) in the little-used key of E Major. Vagaus sings a lullaby, “Umbrae carae, aurae adoratae” (“Beloved shadows, adored breezes”) in which recorders provide the obbligato, as the sweetness of the moment is savored.

Reflections continue with the prayer-like recitative “Summe astrorum Creator” (“Great Creator of the stars”) and Judith’s aria “In somno profundo” (“In deep sleep”). These numbers are accompanied by a consort of viols (four viols and a violone). (Viols were available through benefactions to the Venetian conservatories.)

A renewed sense of vigilance, if not militancy, returns as the Bethulians are summoned in Vagaus’s aria “Armatae face et anguibus,” a “rage” piece calling forth images of snakes, “squalid savages”, and violent death. Ozias is ebullient in “Gaude felix,” a call to rejoice. Judith is acclaimed by the "chorus of virgins" in the closing piece, “Salve, invicta Juditha formosa” (“Hail Judith the Invincible”).

Performer's Guide to Juditha triumphans

Contrary to popular belief, the Pietà's figlie di coro who performed in this and other works by Vivaldi were not nubile. They ranged in age from their mid-teens to their 60s or 70s. Many had pupils who were girls ranging in age from 8 or 10 to their teends. One copy of the libretto for Juditha identifies the soloists as Caterina, Silvia (b. 1650), Polonia (b. 1692), Barbara, and Giulia. All five were born in the seventeenth century, the eldest (Silvia) around 1650, the youngest (Polonia) in 1692. The chorus was one of Virgins with respect both to the Pietà’s situation and in the context of the subject, for Bethulia, the name of the city Judith defended, meant “virgin.”

While in its reliance on core strings (violins, violas, cellos) Juditha triumphans is straightfoward in its instrumental requirements, the obbligati extend to unusual bowed strings (viola d'amore), plucked strings (mandolin, four theorboes), and woodwinds. A consort of five viols (2 treble viols, 2 violas da gamba, and a violone) are called for one in recitativo accompagnato. The woodwinds include paired baroque oboes, recorders, chalumeaux (single-reed instruments that were forerunners of the clarinet). Natural trumpets and timpani lead the triumphal openings and closing numbers.

The Pietà had one chorus, but it could obviously be divided into multiple groups. In Juditha it simply took on a series of colorations--as a chorus of Assyrian soldiers (1.1), servants (1.21A), Bethulians (1.27), drunken (Ottoman) soldiers (2.10), and Judeans (2.28).

The CCARH Edition of Judith triumphans

The CCARH edition of Juditha triumphans, edited by Frances Bennion, Edmund Correia, Jr., and Eleanor Selfrdige-Field, was drafted in 2008 for use by Venice Baroque, one of whose performances may be available {http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2m-zXQNkTi0 here]. The edition has subsequently been revised and corrected for use by Philharmonia Baroque (2014).