Marcello Psalms: Difference between revisions

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

Marcello's explorations of counterpoint were similarly well grounded in the sixteenth century, for in youth he spent considerable amounts of time copying counterpoint treatises by hand. The fruits of his learning are most evident in the later psalms of the last four volumes (V, VI, VII, and VIII containing Psalm Nos. 26-50). No. 36, "Non ti contristi e non ti muova," is one of three offered in what Marcello terms his madrigal style. In all three cases the works are scored for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass without accompaniment, although according to his prefaces "harpsichords and contrabasses" may be used for accompaniment. (The implication here is that he does not want cellos or a standard cello-harpischord basso continuo.) | Marcello's explorations of counterpoint were similarly well grounded in the sixteenth century, for in youth he spent considerable amounts of time copying counterpoint treatises by hand. The fruits of his learning are most evident in the later psalms of the last four volumes (V, VI, VII, and VIII containing Psalm Nos. 26-50). No. 36, "Non ti contristi e non ti muova," is one of three offered in what Marcello terms his madrigal style. In all three cases the works are scored for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass without accompaniment, although according to his prefaces "harpsichords and contrabasses" may be used for accompaniment. (The implication here is that he does not want cellos or a standard cello-harpischord basso continuo.) | ||

Despite his claim of the madrigalesque merits of Psalm 36, it was also one of his most successful exercises in imitative writing. The absence of obbligato instruments and basso continuo left Marcello free to concentrate on voice-leading. Most ornamental devices in music was discouraged by the Council of Trent (1545-1563), but interpretations concerning music encouraged contrapuntal practice insofar as it was conducive to | Despite his claim of the madrigalesque merits of Psalm 36, it was also one of his most successful exercises in imitative writing. The absence of obbligato instruments and basso continuo left Marcello free to concentrate on voice-leading. Most ornamental devices in music was discouraged by the Council of Trent (1545-1563), but interpretations concerning music encouraged contrapuntal practice insofar as it was conducive to contemplation of piety. In this work, which considers treatment of the "ungodly," numerous words receive special treatment. Words that emphasize time, constancy, or eternity are held for several bars. Descending scales accompany sinners. Exaltation requires ascending voices. Three verses (Nos. 22, 31, and 41, all shifting between for soprano/alto and tenor/bass duets) use a common ostinato. A chromatic ostinato for obbligato cellos and basses is offered at Bar 398 to route iniquities. At Bar 441, musical cues for Violone and Contrabasso (double bass) indicate they should double the part of the bass voice. The chromatic ostinato returns at Bar 581. At "Mai giusti" (Bar 624) Marcello pairs the inner voices (alto and tenor) with one imitative entry and its complement is shared by the outer voices (soprano and bass). They eventually agree to share a single subject. When the chromatic ostinato appears for the third time (Bar 732) it provides a bridge to a final elaborately imitative movement that ends the piece. | ||

Sopranos are conpsicuously absent in most of the Psalms. Marcello insisted he was observing the practice in synagogues, where women sat in an upper gallery and did not participate in services. Yet "Qual' anelante" (No. 41, "As the hart panteth"), for two soprano and basso continuo, is one of the most popular pieces from the entire collection. It was reprinted many times in England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its austere successor, "Dal tribunal' augusto" (No. 42, From Thine almighty court) was equally popular. Scored for bass and basso continuo, it became well known through its quotation in [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hawkins_(author) John Hawkins]' quotation in his <i>General History of the Science and Practice of Music</i> (1776). | Sopranos are conpsicuously absent in most of the Psalms. Marcello insisted he was observing the practice in synagogues, where women sat in an upper gallery and did not participate in services. Yet "Qual' anelante" (No. 41, "As the hart panteth"), for two soprano and basso continuo, is one of the most popular pieces from the entire collection. It was reprinted many times in England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its austere successor, "Dal tribunal' augusto" (No. 42, From Thine almighty court) was equally popular. Scored for bass and basso continuo, it became well known through its quotation in [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hawkins_(author) John Hawkins]' quotation in his <i>General History of the Science and Practice of Music</i> (1776). | ||

Revision as of 02:33, 6 January 2018

Marcello's Psalms of David constitute an unusual chapter in the history music. They were collectively published under the title L'estro poetico-armonico: parafrasi sopra li primi [e secondi] venticinque salmi di Davide (Poetic-harmonic fecundity: The first [second] twenty-five Psalms of David) in eight folio (large-format) volumes issued between 1724 and 1726. Catalogues often take the subtitle for the initial title, thus beginning Parafrasi... (Paraphrases...), following the subtitle. In textual sources, the collection is usually cited as the Estro poetico-armonico, while in editions the single works are named and designated psalms.

The Psalms were not intended for liturgical use. It is for this reason that the poetic paraphrases are in the Italian vernacular rather than the Latin. In the composer's mind they were secular works intended to enhance discussion of literary and intellectual themes in explorations of ancient cultures. Each work made its debut at an academic gathering. Musically, the Psalms are atypical of the larger culture in which they existed, for in it opera and chamber music predominated. Yet they are also highly intricate works that reflect in their musical construction the elaborate poetic schemes of David's psalmistry.

God, Man, and Arcadian Values in the Eighteenth Century

The Psalms of David that were published in Venice in eight folio volumes (1724-1726) bring into convergence an array of approaches to composition. Yet all of them pursue a single goal: to suit the antiquity of the subject to allusions to antiquity in the music. Marcello was precocious in adopting this aim. He was a leader among Venetian noblemen in the breadth of his intellect and the depth of his commitment to Antiquarianism. Peter Gay's term "pagan Christianity" (which applies to an impetus of the time) sums up Marcello's methods of appealing of the sensibilities of other enthusiasts of neoclassical culture.

We can see from Sebastiano Ricci's stern depiction of God in the frontispiece of Book III (1724) that Old Testament justice could be harsh. Yet the Psalms that that describe David's prayers and his pleas for mercy provide sharp contrasts for the menacing scenes of fear and efforts to escape God's wrath. Dramatically, the Psalms fluctuate in mood. The notion of a pagan Christianity aptly characterizes the way in which Marcello makes his evocation of the fluctuating relationship of Man to God. His treatment reflects rising interest in classical archaeology and the ancient models of art and literature to which is brought attention. The Biblical figure of King David was known as an articulate poet and a moving orator, although many Psalms express is desolation and supplication.

Psalm Categories and their Vernacular Translations

Like Marcello, Girolamo Ascanio Giustiniani (1677-1732), who composed the vernacular setting of the Psalm texts, was a nobleman. As mayor of Padua (1703), he was well known on the mainland. Giustiniani was the dedicatee of Francesco Gasparini's L'Armomico pratico al cimbalo (1708), a practical manual on keyboard accompaniment. His daughters were harpsichord students of Marcello's. The Giustiniani had a modest palazzo on the Grand Canal in the parish of San Barnabà between the Ca' Rezzonico (today a museum of eighteenth-century art) and the Ca' Foscari (today the nucleus of the University of Venice).

Texts for Marcello's Psalm settings

The musical settings are based on vernacular translations from the original Hebrew by another Venetian nobleman, Gerolamo Ascanio Giustiniani II. The family resided in a modest north-facing palazzo on Venice's Grand Canal in the parish of San Barnabà, and the first performances of the works are thought to have been presented privately in their salon looking onto the water. Since Marcello's time the Psalms have been performed in large numbers of diverse settings. Although not intended as music for worship, the Psalms have been used in churches all over Europe.

Theologians divide the Psalms of David into several thematic cateogories including kingship, the holy city of Zion, songs of trust, songs of thanksgiving, laments, songs for royal feasts (e.g. weddings), meditations on life ("wisdom" songs), and commemorations of historical events. In common with the Pentatuch (the first five books of the Bible), the Psalms are divided (unequally) into five sections but the works are not grouped thematically. However each set closes with a doxology. The works are said to be grouped in five "benedictions": 1-41, 42-72, 73-89, 90-106, 107-150 (Roman Catholic numbering). The scheme may have originated with the editors of the Torah. Over centuries many textual tropes accrued to individual psalms. (The complexities of Psalm numbering systems are explained here.)

Why exactly Giustiniani and Marcello decided to present only 50 of the Psalms is unknown, but two important considerations are evident. Each composition was a significant work in its own right. Also, the number 50 had its own liturgical considerations in Christian theology and liturgy. The celebratory feast of Easter was framed by two periods of 50 days, the two extremes marking the start of Lent, the last the feast of Pentecost. The later celebrated the descent of the Holy Spirit, which was a final link in the formation of the Trinity.

In their original presentation, the Psalms begged for musical treatment. David was a poet and a musician. His texts cited leaders choirmasters, stringed instruments and harps. Lyres of one kind of another had been popularity used in monasteries for many centuries. The stringed instruments in use in Marcello's time were bowed ones of the violin family, not the simpler plucked ones of antiquity.

The Intellectual Network of Psalm Admirers

Marcello anticipated the advent of social networks, for the pan-European Republic of Letters that peaked in his time offered a predecessor. He sent provisional copies of each volume to different learned musicians and reproduced their enthusiastic replies as prefaces to each volumes. The grounding of his quest in the circles of Italy's Arcadian Academy, a network of noblemen and women committed to certain ideals of ancient Greece, helped to facilitate this orientation, but it did not supply him with a large cache of capable musicians. Leading musical figures of of Roman Arcadianism had been Arcangelo Corelli and Bernardo Pasquini, but both were now dead.

Few of the musical correspondents are widely known today, but all were highly respected in their time. Among them the best remembered are Johann Mattheson (1681-1764), the Hamburg Kapellmeister who was also a prolific writer on music, and Georg Philip Telemann (1681-1767), whose commitment in Hamburg was of short duration. Eminent Italian composers included Francesco Gasparini (1661-1727), the maestro di cappella of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome; Geminiano Giacomelli (1692-1740), an organist in Piacenza; Domenico Sarri, a composer in Naples; Antonio (1677-1726, Modena) and Giovanni Bononcini (1670-1747, now in London); and the Italian emigrant composers Francesco Antonio Conti (now in Vienna) and Stefano Andrea Fiorè (in Turin and elsewhere). Others associated with the enterprise, such as Domenico Lazzarini and Girolamo Ascanio Giustiniani were poets and dramatists who were committed to the same ideals as Marcello. They were also had strong ties to Padua. Part of the response to Marcello's Psalms focused on one or another of these testimonial letters. Marcello built an extensive network of contacts to bring his works to public attention. In this effort he was gratifyingly successful.

Separate from the musical response, there was also a literary response to the Psalms. In the Giornale de' letterati d'Italia, Apostolo Zeno (1669-1750) praised both the music and, more particularly, the intricacy of interleaving ancient scripts and non-Western notation into modern print. Zeno duplicated this feat by quoting from one book in his review. to remind us that the poet was more important than the composer, Zeno titled his piece "Psalms paraphrased and dressed in music by Benedetto Marcello" and listed it in the index under G (Giustiniani).

Musical Allusions to Ancient Cultures

The most eye-catching feature of several of Marcello's Psalm settings was the inclusion of facsimiles from traditions of worship in Antiquity (or what was then understood to be ancient). These quotations are confined to Books II, III, and IV (all 1724). Marcello was careful to distinguish an array of different liturgical traditions and, although he was very learned, his examples all seem to have been found in Venice. The Marcello family's modest palazzo (next to the Ca' Vendramin-Calergi, where Richard Wagner later died) was very close to the Ghetto, which was itself divided into an Old Ghetto (to the north) and a New Ghetto (close to the Grand Canal).

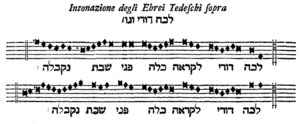

The divisions that interested Marcello were its three Jewish traditions--Ashkenazic (Pss. 15, 17, 19, 21, and 22), Sephardic (Pss. 16, 17, and 18), and Levantine. The German Scola (synagogue) was in the New Ghetto. In Marcello's time it was larger than the other two, which were situated in the continguous Old Ghetto. Israel Adler showed that the earliest exemplars of some of the melodies used by Marcello have no documented history before the the seventeenth century. More recently Don Harran and Edwin Seroussi have mapped the repertories of Marcello's cache of "ancient" chants onto broader terrains of cultural and musical dispersal. Yet each one has a unique history.

Apart from his Jewish exemplars, Marcello also introduced intonations from the Roman Catholic liturgy of his time, and a Greek text said to be be based on Dionysius' Hymn to the Sun. In some psalms, melodies from more than one ancient tradition were used. Marcello's set each verse as a separate movement. This enabled him to draw from highly diverse previous uses of the materials from which he drew.

Intonations (ancient melodies) used in Selected Psalms

Marcello's obsession with melodies symbolic of ancient melody was concentrated in Books II, III, and IV of the Psalms of David (all published in 1724). In Book II (1724) he drew on Sephardic traditions in Psalms 9 and 14, but on the Ashkenazic in No. 10. It was in Book III (1724) that Marcello incorporated the greatest number of selections from earlier traditions. Here too Sephardic examples (Nos. 15, 16, 18) predominated, but No. 14 drew on Ashkenazic usage and No. 17 on both Sephardic and Askenazic. No. 14 also adapted an ostensibly Greek source. In Book IV (still 1724) Marcello completed his excursion into the use of ancient melodic models for inspiration. He leaned mainly on Askenazic practice in Psalms 19, 21, and 22. The materials subsumed in No. 21 were in use by both Italian Sephardi and south German Ashkenazi. Downloadable scores are available below for items starred in the ensuing commentary.

It was one thing to derived new works from ancient melodies but another to employ the derived melodies in ways that corresponded to their use in the underlying source. The texts of the chants Marcello utilizes are usually associated not with the corresponding psalms but with verses from later psalms (Nos. 51-150). In recent writings diverse hypotheses of Marcello's motives have been offered. Don Harrán emphasizes the literary predecessors and evaluates Marcello's debts to numerous music theorists, including Gioseffo Zarlino (1517-1590) and Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680). Edwin Seroussi emphasizes cultural bifurcation and drift to explain lapses between Sephardic and Ashkenazic practice (and even differences between Ashkenazic practices north and south of the Alps. These commentaries are valuable in explaining lapses between Marcello's rendering of his sources and other presentations more readily available today.

Psalm 14: O Signor chi sarà mai?* (Lord, who will dwell in Thy tabernacle?)

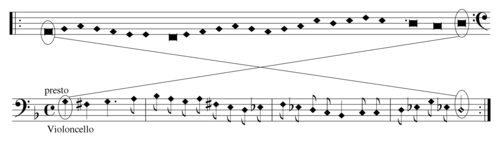

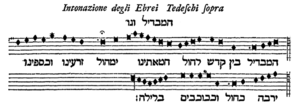

As Marcello's English commentators were careful to explain, Hebrew chant (like text) was regularly notated from right to left. In matching the source to its melodic derivation in Marcello's setting (p. 5 in the linked score facsimile), this must be born in mind. (The backward stems in the cello obbligato replicate the appearance of the older Italian typographical style used in the Psalm prints. At a time when almost all Venetian music was being typeset in Amsterdam in a newer style, Marcello preferred his work to be offered in the diamond-shaped note-heads of sixteenth-century Venetian typesetting. In his transcription Marcello reduced temporal values by 8 (from a breve, or double whole note, to a quarter note).

Marcello uses the Sephardic chant "Odekha ki anitani" (shown below) to derive a verse setting (Verse 5) in this way. The Hebrew text for the intonation (melody) he selects ("I praise you for you have answered me") comes from Psalm 117 (118), Verse 21 ("Confitemini Domino" in the Latin). Marcello's word-painting is well illustrated in this psalm by his choice of an ostinato bass for the preceding verse, which speaks of "the sincere heart untouched by deception".

Psalm 15: Signor, dall’empia gente (Lord, reserve me from the ungodly)

The twelfth-century verse "Ma'oz tzur yeshu'ati" has been associated with multiple melodies. Marcello's version was associated exclusively with Ashkenazic practice. The predominant strain today is used by Judaic communities world-wide.

Psalm 16: Tu che sai quanto sia giusta (Hear my righteous cause)

The borrowing in the setting of the first verse of Psalm 16, scored for two tenors and basso continuo, was described by Marcello as the Hymn of Dionysius to the Sun. It is now attributed to Mesomedes Lyricus, who addresses the "Father of the snowy-lashed Dawn." The psalmist implores the Lord to "Hear my righteous cause." Verse 9 is borrows from the Sephardic chant "Shiru ladonay shir hadash' (Sing unto the Lord a new song). The melody is treated almost as if it were a folk song.

Psalm 17: Io sempre t'amerò (I will always love Thee)

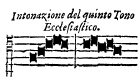

Marcello draws on both Sephardic and Ashkenazic traditions in Psalm 17, which employs alto, tenor, bass, and basso continuo. It is a lengthy psalm, which also incorporates an ecclesiastical intonation on the fifth tone.

Marcello draws on the Sephardic hymn "Ahar nognim 'ashir shirah" (After playing instruments I will sing a song) as a source for the melody in Verse. Verse 54 derives its melody from an Ashkenazic benediction, "Ha-mavdil bein quodesh le-hol" (May he who separates the sacred from the profane forgive our sins.)

Psalm 18: I Cieli immensi narrano* (The Heavens are telling)

Marcello's setting of Psalm 18 was widely circulated throughout the nineteenth century. It incorporated three verses inspired from examples thought to be ancient. The English title is the same as that of jubiland chorus in Haydn's oratorio The Creation.

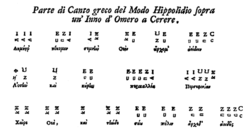

The music of Verse 15 was derived, according to Marcello, on "the Greek hymn of Homer to Ceres." The text, taken from Gaudentius, was addressed to Demeter and "her beautiful daughter" Persephone.

Ferdinando Paer (1771-1839) produced an orchestrated version of the work. A keyboard arrangement by Georges Bizet (1838-1875) was published in 1865.

Psalm 19: Quando, o Re, cinto sarai dagl’affanni? (When will the Lord hear Thee?)

Psalm 19, set for alto, tenor, two basses, and basso continuo, was another work that inspired imitations. The origin of this source is contentious. The succeeding verse was introduced by an ecclesiastical intonation on the fourth tone. An organ transcription of the first verse by [Alexandre Guilmant] (1837-1911) was published in Leipzig in the 1890s.

Psalm 21: Volgi, mio Dio (My God, o look upon me)

Although the origins of the quoted intonation in Verse 20 is controversial, this psalm was also fertile ground for composers of the nineteenth century. In 1826 Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) derived the "Greek" funeral march in his opera La Siège de Corinthe from this piece, although he was acquainted with it from [1] Simone Mayr's use in his Samuele (1821).

Psalm 22: S’è il Signore, mio pastore* (The Lord is my shepherd)

This familiar psalm is set for alto, tenor, and basso continuo. While Marcello served as chancellor in Brescia (1738-1739) his wife, the singer Rosanna Scalfi is known to have performed this work. Verse 6 derives its melody from the Ashkenazic chant "Yitgadal v'yitqadash sh'me raba."

Scoring, madrigalisms, and countrapuntal usage in the Psalms

Marcello's attraction to classical models also led to close study of the madrigal and of contrapuntal practice in the sixteenth century. Although his investment in madrigals seems to have been concentrated in his Op. 4 of 1717, madrigalisms are found abundantly in his all of his secular vocal music extending to the Psalms of David, and also in his madrigals. It happens too that some [Biblical] figures of speech in the Psalms exert influence over his two late oratorios--Il pianto e il riso delle quattro stagioni and Il trionfo della poesia e la musica--which heavily rely on secular imagery.

Marcello's explorations of counterpoint were similarly well grounded in the sixteenth century, for in youth he spent considerable amounts of time copying counterpoint treatises by hand. The fruits of his learning are most evident in the later psalms of the last four volumes (V, VI, VII, and VIII containing Psalm Nos. 26-50). No. 36, "Non ti contristi e non ti muova," is one of three offered in what Marcello terms his madrigal style. In all three cases the works are scored for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass without accompaniment, although according to his prefaces "harpsichords and contrabasses" may be used for accompaniment. (The implication here is that he does not want cellos or a standard cello-harpischord basso continuo.)

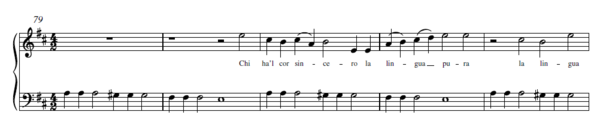

Despite his claim of the madrigalesque merits of Psalm 36, it was also one of his most successful exercises in imitative writing. The absence of obbligato instruments and basso continuo left Marcello free to concentrate on voice-leading. Most ornamental devices in music was discouraged by the Council of Trent (1545-1563), but interpretations concerning music encouraged contrapuntal practice insofar as it was conducive to contemplation of piety. In this work, which considers treatment of the "ungodly," numerous words receive special treatment. Words that emphasize time, constancy, or eternity are held for several bars. Descending scales accompany sinners. Exaltation requires ascending voices. Three verses (Nos. 22, 31, and 41, all shifting between for soprano/alto and tenor/bass duets) use a common ostinato. A chromatic ostinato for obbligato cellos and basses is offered at Bar 398 to route iniquities. At Bar 441, musical cues for Violone and Contrabasso (double bass) indicate they should double the part of the bass voice. The chromatic ostinato returns at Bar 581. At "Mai giusti" (Bar 624) Marcello pairs the inner voices (alto and tenor) with one imitative entry and its complement is shared by the outer voices (soprano and bass). They eventually agree to share a single subject. When the chromatic ostinato appears for the third time (Bar 732) it provides a bridge to a final elaborately imitative movement that ends the piece.

Sopranos are conpsicuously absent in most of the Psalms. Marcello insisted he was observing the practice in synagogues, where women sat in an upper gallery and did not participate in services. Yet "Qual' anelante" (No. 41, "As the hart panteth"), for two soprano and basso continuo, is one of the most popular pieces from the entire collection. It was reprinted many times in England in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its austere successor, "Dal tribunal' augusto" (No. 42, From Thine almighty court) was equally popular. Scored for bass and basso continuo, it became well known through its quotation in John Hawkins' quotation in his General History of the Science and Practice of Music (1776).

Reception, Subsequent Editions, and Adaptations

Through the year 2013, at least 23 complete editions of Marcello's Psalms of David have been published. Only three of these reissues (1776, 1803-05, 1835) come from Venice. The first foreign use occurred in Prague (1729), when several passages based on ancient materials were incorporated into a Lenten oratorio by Antonio Denzio (1689-after 1767) on the subject of Samson.

Performances and editions of the complete set of 50 Psalms followed in Rome (1739). Parisian prints of the nineteenth century, such as the edition of Madam Launer in Paris (1841), which had a piano accompaniment by Francisek Mirecki and lyrics in French, attracted the interest of Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842), Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), Ferdinando Paer (1771-1839), and Georges Bizet (1838-1775). Over time Giustiniani's texts were translated into German, French, Swedish, English, Czech, and Church Latin (for ecclesiastical use).

Marcello's Psalms were inordinately popular in England. In particular they were championed by the Newcastle organist Charles Avison (1709-1770), who was won over by their "sublime harmonies". (In France, Marcello's Psalms were praised by their counterpoint, in Germany for their melodies.) Avison labored intensely in the preparation of an eight-volume edition with English lyrics. The series was published by John Garth, the organist of Durham Cathedral, in 1757.

Avison provided a biography of Marcello in the first volume of the Garth edition. "The Psalms," Avison wrote, "are so excellent, and the great and affecting touches of nature and art so numerous, that few subjects of censure will be found. They appear to me fraught with every musical beauty." It was her that Avison stated that he had found the harmonies of the works their outstanding quality. As a composer of concertos and sacred vocal music, Avison had a direct interest in the harmonic aspects of music. His Essay on Musical Expression (1752) had been the first of its kind in English. He was an also enthusiast of Italian music styles.

Downloadable Scores

These scores were edited by Don Anthony, who typeset the music, in collaboration with Eleanor Selfridge-Field.

| Psalm | Title | Translation | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | O Signor, chi sarà mai? | Lord, who will dwell in Thy tabernacle? | Ps. 14 |

| 18 | I Cieli immensi narrano | The Heavens are telling | Ps. 18a |

| 18b | In omnem terram | In all the earth | Ps. 18b |

| 22 | S'è il Signore, mio pastore | The Lord is my shepherd | Ps. 22 |

| 36 | Non ti contristi e non ti muova | Fear not the ungodly | Ps. 36 |

Bibliography

- Bizzarini, Marco. Benedetto Marcello. Palermo: L'Epos, 2006. ISBN 978-888-3022968.

- án, Don. "Hebrew exemplum as a force of Renewal in 18th-century Musical Thought: The Case of Benedetto Marcello and his Collection of Psalms" in Andreas Giger and Thomas Matthiesen, Music in the Mirror: Reflections on the History of Music Theory and Literature for the 21st Century, Publications of the Center for the History of Music Theory and Literature,3, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 143-194.

- Jonášová, Milada. " 'Intonazione degli Ebrei' from Benedetto Marcello's Estro poetico-armonico in Prague in 1729," Etnologický ústav AV ČR, v.v.i. (Prague, 2015), pp. 9-54).

- Selfridge-Field, Eleanor. The Works of Benedetto and Alessandro Marcello: A Thematic Catalogue with commentary on the Composer, Repertory, and Soruces (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990).

- Selfridge-Field, Eleanor. "Marcello's orientalism" in Psalmen: Kirchenmusik zwischen Tradition, Dramatik, und Experiment, ed. Helen Geyer and Brigit Johanna Wertenson (Cologne: Bohlau, 2014), 205-222.

- Seroussi, Edwin. "In Search of Jewish Musical Antiquity in the 18th-Century Venetian Ghetto: Reconsidering the Hebrew Melodies in Benedetto Marcello's 'Estro Poetico-Armonico'," The Jewish Quarterly Review, new series, 93 (2002), No. 1/2, 149-199.

Credits

Copyright 2017 Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities, an affiliate for the Packard Humanities Institute. Content: Eleanor Selfridge-Field. Typesetting of modern facsimiles from the originals prints: Don Anthony. Technical support: Craig Sapp. Editorial support: Edmund Correia Jr. and Ilias Chrissochoidis. Musicological advice: Milada Jonášová and Marco Bizzzarini. Contextual advice on Jewish musical, literary, liturgical practices: Edwin Seroussi and the late Don Harrán.