Marcello Psalms: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

Marcello was a master of networking in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accademia_degli_Arcadi Arcadian Academy], a network of noblemen and women committed to certain ideals of ancient Greece. Much of pastoral imagery in art and music reflected this stance. The primary instance of Arcadia issued from the hills of the Janiculum in seventeenth-century Rome. Upon her passing, many cities of the Italian peninsula established their groups who explored explored poetry and music through verse, cantatas, and serenatas. Leading figures in Rome were [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arcangelo_Corelli Arcangelo Corelli] and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernardo_Pasquini Bernardo Pasquini]. | Marcello was a master of networking in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accademia_degli_Arcadi Arcadian Academy], a network of noblemen and women committed to certain ideals of ancient Greece. Much of pastoral imagery in art and music reflected this stance. The primary instance of Arcadia issued from the hills of the Janiculum in seventeenth-century Rome. Upon her passing, many cities of the Italian peninsula established their groups who explored explored poetry and music through verse, cantatas, and serenatas. Leading figures in Rome were [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arcangelo_Corelli Arcangelo Corelli] and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernardo_Pasquini Bernardo Pasquini]. | ||

In planning their publication (in eight handsome foglio volumes issued by Domenico Lovisa, 1724-26), Marcello took the unusual step of soliciting testimonials from leading composers, music masters, and noted poets and dramatists. He included a few of these testimonials in each volume. | In planning their publication (in eight handsome foglio volumes issued by Domenico Lovisa, 1724-26), Marcello took the unusual step of soliciting testimonials from leading composers, music masters, and noted poets and dramatists. He included a few of these testimonials in each volume. | ||

Among the respondents, the best remembered today are [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Mattheson Johann Mattheson] (1681-1764), the Hamburg <i>Kapellmeister</i> who was also a prolific writer on music, and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Philipp_Telemann Georg Philip Telemann] (1681-1767), Hamburg's most prolific composer. Eminent Italian composers included [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francesco_Gasparini Francesco Gasparini] (1661-1727), the <i>maestro di cappella</i> of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geminiano_Giacomelli Geminiano Giacomelli] (1692-1740) (Piacenza), Domenico Sarri (Naples), Antonio (1677-1726, Modena) and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Bononcini Giovanni Bononcini] (1670-1747, London), and the emigrant composers Francesco Antonio Conti (Vienna) and Stefano Andrea Fiorè (Turin). The rest (including Domenico Lazzarini and Girolamo Ascanio Giustiniani) were poets and dramatists allied with Marcello's ideals. | Among the respondents, the best remembered today are [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Mattheson Johann Mattheson] (1681-1764), the Hamburg <i>Kapellmeister</i> who was also a prolific writer on music, and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Philipp_Telemann Georg Philip Telemann] (1681-1767), Hamburg's most prolific composer. Eminent Italian composers included [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francesco_Gasparini Francesco Gasparini] (1661-1727), the <i>maestro di cappella</i> of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geminiano_Giacomelli Geminiano Giacomelli] (1692-1740) (Piacenza), Domenico Sarri (Naples), Antonio (1677-1726, Modena) and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Bononcini Giovanni Bononcini] (1670-1747, London), and the emigrant composers Francesco Antonio Conti (Vienna) and Stefano Andrea Fiorè (Turin). The rest (including Domenico Lazzarini and Girolamo Ascanio Giustiniani) were poets and dramatists allied with Marcello's ideals. | ||

Benedetto Marcello was physically distant but intellectually close to Rome's Arcadia. He strove to implant Arcadian value in music. His 379 cantatas for solo voice, almost 100 for two voices, and various works for 3-5 voices were intended for performance at weekly gatherings of individual colonies. The social practice underlying these gatherings waned in Italy by 1750, but his secular music found its way into other assemblies all over Europe, where it enjoyed respect through much of the nineteenth century. | |||

Revision as of 00:57, 18 November 2017

The Psalms of David that were published in Venice in eight folio volumes (1724-1726) bring into convergence an array of approaches to composition. Yet all of them pursue a single goal: to suit the antiquity of the subject to allusions to antiquity in the music. Peter Gay's term "pagan Christianity" sums up Marcello's methods of appealing of the sensibilities of other enthusiasts of "classical culture." Among other composers, Marcello was precocious in adopting this aim. Among Venetian noblemen, he was a leader in the breadth of intellect and the depth of his commitment.

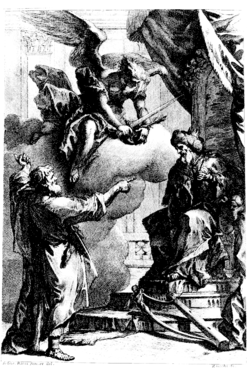

We can see from Sebastiano Ricci's stern depiction of God in the frontispiece of Book III of the Psalms that Old Testament justice could be harsh. Yet the Psalms that that describe David's prayers and his pleas for mercy provide sharp contrasts for the menacing scenes of fear and efforts to escape God's wrath. The term "pagan Christianity" characterizes Marcello's evocation of a vast drama of of the relationship of Man and God. For Arcadians, the emphasis is truly on the expression of the mood of the moment and its apt accommodation in suitable music.

Marcello's Psalms of David constitute an unusual story in the history music. They are widely misunderstood to be sacred works. In the composer's mind they were secular works intended to enhance discussion of literary and intellectual themes popular in Arcadian circles. All of them had their debut performances at academic events.

Marcello was a master of networking in the Arcadian Academy, a network of noblemen and women committed to certain ideals of ancient Greece. Much of pastoral imagery in art and music reflected this stance. The primary instance of Arcadia issued from the hills of the Janiculum in seventeenth-century Rome. Upon her passing, many cities of the Italian peninsula established their groups who explored explored poetry and music through verse, cantatas, and serenatas. Leading figures in Rome were Arcangelo Corelli and Bernardo Pasquini.

In planning their publication (in eight handsome foglio volumes issued by Domenico Lovisa, 1724-26), Marcello took the unusual step of soliciting testimonials from leading composers, music masters, and noted poets and dramatists. He included a few of these testimonials in each volume.

Among the respondents, the best remembered today are Johann Mattheson (1681-1764), the Hamburg Kapellmeister who was also a prolific writer on music, and Georg Philip Telemann (1681-1767), Hamburg's most prolific composer. Eminent Italian composers included Francesco Gasparini (1661-1727), the maestro di cappella of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, Geminiano Giacomelli (1692-1740) (Piacenza), Domenico Sarri (Naples), Antonio (1677-1726, Modena) and Giovanni Bononcini (1670-1747, London), and the emigrant composers Francesco Antonio Conti (Vienna) and Stefano Andrea Fiorè (Turin). The rest (including Domenico Lazzarini and Girolamo Ascanio Giustiniani) were poets and dramatists allied with Marcello's ideals.

Benedetto Marcello was physically distant but intellectually close to Rome's Arcadia. He strove to implant Arcadian value in music. His 379 cantatas for solo voice, almost 100 for two voices, and various works for 3-5 voices were intended for performance at weekly gatherings of individual colonies. The social practice underlying these gatherings waned in Italy by 1750, but his secular music found its way into other assemblies all over Europe, where it enjoyed respect through much of the nineteenth century.