Messiah: Difference between revisions

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

Over time the differences from one version to another can be said most often to reflect changes in voicing or orchestration. A few pieces became shorter with revision. There was a slight increase in the use of choral material, although the choruses were by far the most stable elements of the work. There is no formula by which these tendencies can be broadly applied. <i>Messiah</i>'s continuous state of evolution leaves many open questions for today's performers. | Over time the differences from one version to another can be said most often to reflect changes in voicing or orchestration. A few pieces became shorter with revision. There was a slight increase in the use of choral material, although the choruses were by far the most stable elements of the work. There is no formula by which these tendencies can be broadly applied. <i>Messiah</i>'s continuous state of evolution leaves many open questions for today's performers. | ||

====Identifiable Versions==== | ====Identifiable Versions of <i>Messiah</i> from Handel's Lifetime==== | ||

In the case of <i>Messiah</i>, the number of sources surviving from Handel's own time is fewer than the number of documented productions. [1,2] Discrepancies are first noted between Handel's autograph (summer 1741) and the libretto for the first public performance (April 1742). [3-6] Librettos map changes from year to year, but the music for all the Covent Garden performances issues largely from one manuscript source. [7] While it is known that Handel's himself participated in performances at the Foundling Hospital from 1754 onward, only the performing parts survive. [8] Handel's conducting score is a valuable source for mapping changes in his thinking and documenting his own idea of a best version. [9] The 1761 manuscript by James Matthews is regarded as contemporary with Handel's own versions because Matthews sang in multiple productions of the work. | |||

1 Handel's autograph manuscript (1741) | |||

2 Libretto for first public version (Dublin 1742) | |||

3 Covent Garden libretto for first English version (1743) | |||

4 Covent Garden libretto (1745) | |||

5 Covent Garden libretto (1749) | |||

6 Covent Garden libretto (1750) | |||

7 Foundling Hospital performances (1754-59), parts (1759) | |||

8 Handel's conducting score (<i>c</i>. 1758) | |||

9 Manuscript of James Matthews (chorister) (1761) | |||

===The Foundling Hospital Parts for <i>Messiah</i>=== | ===The Foundling Hospital Parts for <i>Messiah</i>=== | ||

Revision as of 00:11, 16 December 2011

Messiah (HWV 56) Composed by George Frideric Handel

Overview

Handel's most famous and most often performed work is the oratorio Messiah, composed in 1741 and first performed in Dublin in 1742. Many individual numbers within the work have become independently familiar.

As it comes to us in the twenty-first century, Messiah is unusual in several respects. Its text suggest that it is a sacred work, but it has enjoyed a substantial life as concert fare. A north German in the service of the British crown, Handel's oratorios were symbols of the (protestant) Church of England and its stature in British society. Dublin, which we know today as the capital of Eire (Ireland), was heavily dominated in Handel's time by English gentlemen.

Handel's Messiah

Handel's famous oratorio Messiah comes down to us the best known and most widely performed of his compositions. Its fame rests of many factors--its gestation under favorable social circumstances in his, its versatility and easy availability in ours. Overriding these extraneous factors is the virtue of the music itself: majestic and contrite by turns, carefully balanced throughout, and within the capabilities of diligent amateurs. This website provides copious performing materials for Messiah, with substantial background information concerning the rubrics on which these materials are based.

Although the story that it narrates (prophecies and events related to the life of Jesus, together with their impacts on human salvation) is a religious one that projects the theological views of Handel's contemporary Charles Jennens, its musical recognition greatly exceeds the boundaries of the English Protestantism in which it originated.

The Architecture of Messiah

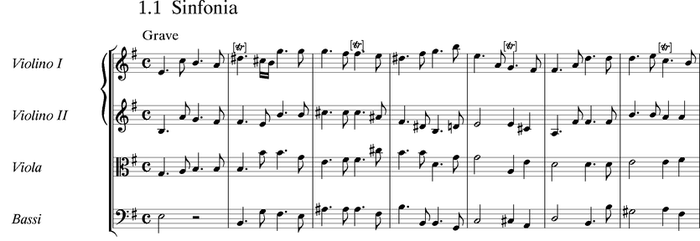

The oratorio consists of three parts: (1) music narrating highpoints from the prophecy of Isaiah to the early life of Jesus; (2) Jesus's birth, death, and resurrection; and (3) the sins and judgment of mankind. Each of these can be parsed into several scenes. Handel's choruses serve as a good guide to the many segments of the work.

In Part One the choruses are these:

1.4 And the glory of the Lord

1.7 And He shall purify

1.10 O Thou that tellest

1.13 For unto us a child is born

1.19 Glory to God in the highest

1.23 His yoke in easy

All are present in the autograph manuscript of 1741. All are scored for four-voice choir (soprano, alto, tenor, bass), and all have string accompaniment. Trumpets are required in "Glory to God in the highest," and oboes were added in later revisions.

The same principles pertain to the remaining choruses of the work (with one exception*): all of them originate in the 1741 autograph. Part Two has the largest number of choruses and culminates with the great "Halleluiah" chorus. Where they overlap with choruses, adjustments to solo parts caused some variability of scoring from version to version.

2.1 Behold the Lamb of God

2.3 Surely, surely; And with his stripes

2.4 All we like sheep

2.6 He trusted in God

2.11 Lift up your heads

2.13 Let all the angels of God worship Him

2.16 Their sound is gone out*

2.18 Let us break their bonds

2.21 Hallelujah

The movement we term 2.16* in our edition exists in five versions and the the chorus indicated here first occurs as a separate one in 1745. The segmentation of the text and the portions assigned to soloist and chorus vary from case to case, both before and after 1745. (Details are given in the downloadable list of versions from Handel's lifetime.) Oboes are also called for in this later accretion. The "Halleluia" chorus includes parts for trumpets and timpani.

Part Three is much simpler in its structure. Its choruses are these:

3.2 Soli, Chorus: Since by man came death (with soloists)

3.7 But thanks be to God

3.9 Worthy is the Lamb

3.10 Amen

Trumpets and timpani are required in the final chorus and concluding "Amen."

The Halleluia Chorus

Messiah is especially noted for its choruses. These are noted for their imitative vocal entries, which contribute to cascades of contrapuntal complexity as various groups of instruments highlight particular passages or counter vocal entries with musically independent passages.

The most famous and most widely heard of these is the Halleluia Chorus, which concludes the second part of the work.

Messiah during Handel's Lifetime

Although Handel had imagined when he composed the work in the summer of 1741 that Messiah would be performed in London. An invited stay in Dublin began in November led to a series of subscription concerts that were wildly successful. In consequence a second series was launched on February 17, 1742. Starting with a performance of Alexander's Feast, the new series continued on Wednesdays through April 7, when the featured work was a revised version of Esther.

Messiah's first performance was an open rehearsal of Messiah that took place the day after the second series finished. Its official premiere the following Tuesday (April 13, at noon) was an anticlimax, and the open rehearsal caused Messiah to be declared "the finest Composition of Musick that ever was heard." The premiere simply confirmed this lofty evaluation.

Background to Handel's Visit to Dublin

Messiah had come into being at the request of Dublin's Charitable Infirmary to compose a work to encourage contributions to the "Dublin sick." At the time hospitals were used more to separate the sick from the rest of society than to treat their maladies. When Messiah had its final Dublin performance, on June 3, there were some changes of cast and organ concertos were performed with it. Other concerts filled the intervening weeks. Among them were a benefit for the Dublin music publishers William and Bartholomew Mainwaring, and Handel's oratorio Saul. Its Dead March became an instant favorite.

Reception and Performance History

The performance history of Messiah between its composition in September 1741 and Handel’s death in April 1759 is rich and constantly changing. Messiah's most persistent detractor was Charles Jennens, its librettist. Handel’s original setting was weak and unsatisfactory. He begged the composer many times to remedy its perceived defects. In January 1743 Jennens wrote to his friend Edward Holdsworth,

| Messiah has disappointed me, being set in great haste, tho’ [Handel] said he would be a year about it, and make it the best of all his Compositions. I shall put no more Sacred Words into his hands, to be thus abus’d. |

Six weeks later he wrote further on the subject,

| ‘Tis still in his power by retouching the weak parts to make it fit for publick performance; and I have said a great deal to him on the Subject; but he is so lazy and so obstinate, that I much doubt the Effect. |

Jennens’ allowed in 1743 that “in the main” Messiah was “a fine Composition,” but he continued to pressure Handel to make changes. And Handel did, so much so that the work was never entirely stable until the composer’s death. Some of the changes responded to Jennens’ wishes, but other simply accommodated changes in casting. In August 1745 Jennens reported to Holdsworth

| I have with great difficulty made him correct some of the grossest faults in the composition, but he retained his Overture obstinately in which there are some passages far unworthy of Handel, but much more unworthy of Messiah. |

The oratorio attracted a growing following in the cathedrals and choral societies of the Western counties and into Wales. In England the choruses of Messiahbecame especially celebrated. Under the direction of William Boyce, there was a performance in Hereford Cathedral in September 1750. A month later the work was given in Salisbury Cathedral. Performances in Bristol, Gloucester, and Leicestershire occurred between 1757 and 1759. Many performances of excerpts were given by the Hereford, Gloucester, and Worcester choral societies.

As the work became more widely circulated, its component parts were subject to change, although the choruses were entirely stable. Although Handel continued to experiment with the work, some numbers that had been changed in the 1740s were restored to their original condition in the 1750s. Twelve distinct productions (most consisting of two or three performances) can be counted between 1743 and March 1759.

Dublin Performances

To its first audience in Dublin Messiah was a resounding success, for it achieved a great charitable goal: poor debtors were released from prison in proportion to its financial success. The composer and two singers of the original cohort donated their share of the proceeds to this cause. Nine performances in Dublin can be dated between the premiere on April 13, 1742, and an Advent performance on December 16, 1756. All of them seem to have met with the “universal applause” merited by the subject, the setting, and the qualities of the performances. All were benefits.

Although there was a performance on June 3, 1742, and February 1, 1744, it appears that from 1745 onward Messiah was an Advent work in Dublin. The actual number of special and seasonal performance there within Handel’s lifetime must easily have reached fifteen. Handel was present for the premiere, but in subsequent years others were in charge. G. B. Marella was the conductor in the 1750s. The performing tradition in Dublin is less well documented than in England. We can be sure, though, that Messiah was invariably well received there. Attendees traveled tens of miles to witness the performance, year in and year out.

London Performances: Covent Garden

Initially, Messiah’s main roost in London in the 1740s was the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden. In England the work was considered a Passion oratorio. [Its first performance, marked neither Advent nor Passion, since it took place almost four weeks after Easter (March 25 in 1742).] The first performance in London took place on March 23, 1743. The initial reception was more mixed than in Dublin. The cause of charity was absent. Some influential attendees regarded passages of the text setting as insensitive to the meaning of the words.

Covent Garden was, of course, an opera house. Protestant England was more lax about opera performances during Lent than were Catholic countries, but oratorios offered a convenient compromise by way of the genre’s ambiguity. Musically, both consisted primarily of an opening sinfonia, arias, and recitatives. In Handel’s case, the differences between opera and oratorio were spelled out by their texts and the portions of it that were strongly emphasized musically. Handel also provided many choruses, and on the whole these would have been much fewer in opera. Jennens’ had had a strong desire to promote his singular idea of “kingship” in the musical realization of Messiah, and in this regard Handel did not fail him: the “king of kings” theme is put in high relief in the "Halleluia" Chorus, which has always been Messiah’s most highly prized element.

London Performances: The Foundling Hospital

London's Foundling Hospital, established on Bloomsbury Fields in 1739, mirrored in its aims the well established institutions for orphans in Italy and France. The most famous of these was the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, where all the orphans were female and where a select group reached the stature of musical professionals under the tuition of such maestri as Antonio Vivaldi and Giovanni Porta.

Such institutions fostered strong musical allegiances because the noble families who supported them believed that music bettered the soul. They particularly cherished music made well by children. The Foundling Hospital's benefactors include such noted painters as Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, and Handel himself. The composer provided an organ and gave benefit performances at the Hospital. At his death, a valuable set of performance parts fell became the possession of the institution. Today the park known as "Coram's Fields" marks the spot where the original Hospital stood.

The Foundling Hospital performances of Messiah, which began in May 1749, were perhaps the most celebrated of all those given during Handel’s lifetime. Like the Dublin performances, they were benefit concerts. Unlike the majority of Dublin concerts, they enjoyed Handel’s direct participation at the organ. Even after he was beset by blindness in 1752, the composer continued to provide an organ concerto. Eleven such performances, most associated with the feast of Ascension (forty days after Easter) are clearly documented.

Oxford and Cambridge Performances

Messiah had a slightly different identity in Oxford, where it was performed in April 1749 at the Radcliffe Camera. It was also given complete performances in the Sheldonian Theatre (where Handel's Athalia had had its premiere in 1733) as part of the commemoration festivities of July 1754 and July 1759. Starting in 1755, various parts of Messiah were performed separately for subscription concerts in the Holywell Music Room. One memorial performance was given at Senate House, Cambridge, under John Randall (later a music publisher) in May 1759.

Monumental Editions of Messiah

Because of the immediate popularity of individual choral and vocal numbers in Messiah, the work was rapidly circulated and adapted to varying circumstances. The rise of choral societies in the third quarter of the century had a symbiotic relationship with Handel's masterpiece. The more the work was performed, the greater the number of groups performing it. Inevitably, each new venue created its own opportunities and limitations. Soloists and sometimes keys of particular pieces could be altered. Orchestration accommodated the resources available. On the whole, the size both increased.

These trends continued in the nineteenth century such that by the time of the Crystal Palace Exposition (in London in xx) the proportions reached what seems to have been their maximum extent: xx.

The Arnold Edition of Handel's Works

Editions of Handel’s music proliferated after the composer’s death. Samuel Arnold was the first person to collect all of Handel’s then-known music and publish it. As a composer Arnold was best known for his Psalms of David (1791), several oratorios, and a few operas. He was a harpsichordist at Covent Garden for many years. In 1793 he was appointed organist of Westminster Abbey, where he was buried in 1802.

His edition of Messiah appeared in 1790. It contains much richer figuration of the basso continuo than earlier versions. This is likely to reflect the reduced training that accompanists were receiving in the “realization” of the sketch of accompaniment that a continuo part otherwise provided. A more detailed prescription was required.

The Händel-Gesellschaft (HG) Edition

In 1858 work was began on the more extensively “complete” works that were produced by the Händel-Gesellschaft (Georg Friedrich Händels Werke) under the direction of Friedrich Chrysander. By its completion in 1902 it contained 94 volumes (several in two tomes) and five supplements. Chrysander also edited all the published works of Arcangelo Corelli (now available in PDFs with associated MIDI files at http://corelli.ccarh.org), Bach’s keyboard works, and Palestrina’s motets.

Chrysander's edition of Messiah appeared Vol. 45 (1902). It can be downloaded from the website of the Munich Digitalization Center (part of the ViFaMusik project) at http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0001/bsb00016880/images/index.html.

The Hallische Händel Ausgabe (HHA)

The current effort to publish all known music by Handel resides with the edition managed in Halle, Germany. It was initiated in 1952 with the intention of supplementing HG, but discoveries continue to be made, and in 1958 it was launched as a new edition. Although it was through most of its publication history signaled by the letters HHA, these have now been superseded by the use of Baselt's Handel catalogue of works (HWV for the Händel-Werke-Verzeichnis).

The MuseData Edition of Messiah

Multitudes of stand-alone editions of Messiah exist. The MuseData edition, undertaken by the Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities in cooperation with Philharmonia Baroque in 1989, was intended to produce a collection of performing materials that represented all versions of the work known through the time Handel died in 1759.

Versions and Sources (1741-1759)

Eighteen manuscript sources are regarded as pertinent to early performances, but surviving source material and documented performances do not match on a 1:1 basis. Numerous eye-witness accounts of individual performances suggest that we will never know every detail of any one of them. Some known performances are survived by no sources. Multiple performances with differences between them may need to be traced through the complex fabric of a single, many-times-altered source. Otherwise valuable early materials postdate Handel’s death and may reflect the opinions and preferences of the transcriber. A best-guess effort to define Handel's last thoughts on the

Over time the differences from one version to another can be said most often to reflect changes in voicing or orchestration. A few pieces became shorter with revision. There was a slight increase in the use of choral material, although the choruses were by far the most stable elements of the work. There is no formula by which these tendencies can be broadly applied. Messiah's continuous state of evolution leaves many open questions for today's performers.

Identifiable Versions of Messiah from Handel's Lifetime

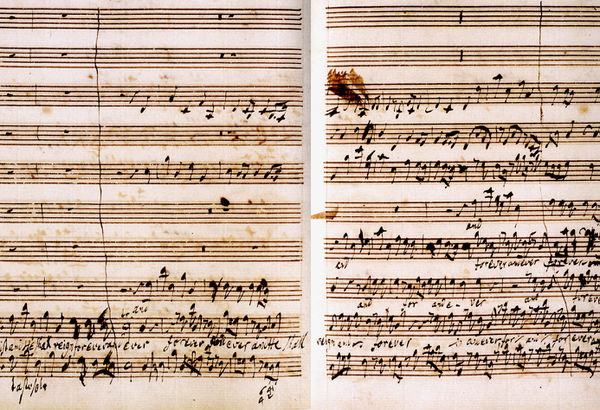

In the case of Messiah, the number of sources surviving from Handel's own time is fewer than the number of documented productions. [1,2] Discrepancies are first noted between Handel's autograph (summer 1741) and the libretto for the first public performance (April 1742). [3-6] Librettos map changes from year to year, but the music for all the Covent Garden performances issues largely from one manuscript source. [7] While it is known that Handel's himself participated in performances at the Foundling Hospital from 1754 onward, only the performing parts survive. [8] Handel's conducting score is a valuable source for mapping changes in his thinking and documenting his own idea of a best version. [9] The 1761 manuscript by James Matthews is regarded as contemporary with Handel's own versions because Matthews sang in multiple productions of the work.

1 Handel's autograph manuscript (1741)

2 Libretto for first public version (Dublin 1742)

3 Covent Garden libretto for first English version (1743)

4 Covent Garden libretto (1745)

5 Covent Garden libretto (1749)

6 Covent Garden libretto (1750)

7 Foundling Hospital performances (1754-59), parts (1759)

8 Handel's conducting score (c. 1758)

9 Manuscript of James Matthews (chorister) (1761)

The Foundling Hospital Parts for Messiah

Score and Parts

- Full Score (2003 version), 280 pages.

- Parts: Violin 1, Violin 2, Viola, Basso continuo

- Continuo part (2003 version), with figured harmony based on the Samuel Arnold Edition of 1790, 101 pages.

- Expanded Continuo part (2003 version), with figured harmony based on the Samuel Arnold Edition of 1790, 197 pages. Included continuo part plus treble staff with melodies and primary voices.

- Choral score (1990 version). Movements with vocal parts, plus first violin and basso continuo parts.

- Full Score (1990 version), 404 pages.

References

Baselt, Bernd. Dokumente zu Leben und Schaffen, v. 4 of the Händel-Handbuch Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1985.

Beeks, Graydon. "Messiah Anniversary," Newsletter of the American Handel Society,/i> (August 1991), pp. 1-5. Reproduced at http://www.americanhandelsociety.org/documents/Summer1991.pdf.

British Library: Autograph Manuscript [R.M.20.f.2] of Handel’s Messiah (as a “virtual book”): http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/virtualbooks/detect.html?id=38FD72B2-5B98-4FC2-AAAE-98E717E8D512&accessfolder=handel

Burrows, Donald. “'Mr. Harris's score': A new look at the 'Mathews' manuscript of Handel's Messiah,” Music & Letters, (2005), 86(4) 560-572.

Burrows, Donald. “The autographs and early copies of Messiah: Some further thoughts, Music & Letters (July 1985), 66(3) 201-19.

Larsen, Jens Peter. Handel’s Messiah. New York, 1972.

McGegan, Nicholas. "Which Messiah?," Musical Times, 133(1797) 577-579.

Marx, Hans Joachim. “Die 'Hamburger' Direktionspartitur von Händels Messiah,“ [“The Hamburg Conducting Score of Handel’s Messiah“], Festschrift Klaus Hortschansky zum 60. Geburtstag [Festschrift for Klaus Hortschansky on his 60th birthday]. Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1995, pp. 131-138. ISBN: 3-7952-0822-X.

Shaw, Watkins. A textual and historical companion to Handel's Messiah, Sevenoaks (UK), 1965. Rev. edn., 1982.

Shaw, Watkins. “Handel's Messiah: Supplementary notes on sources,” Music & Letters (August 1995), 76(3) 356-368.

The complete Händel-Gesellschaft edition is available in digital files from the Munich Digitalization Center’s website: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1193214396&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig