MuseData: Arcangelo Corelli: Difference between revisions

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

! Composer !! Arranger genre !! Corelli genre !! Corelli ID !! Arranger source | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Geminiani || Concerto grosso || Sonata da chiesa || Op. 3, n. 1 || Walsh #569 | | Geminiani || Concerto grosso || Sonata da chiesa || Op. 3, n. 1 || Walsh #569 | ||

Revision as of 00:32, 5 June 2024

The music of Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) exerted a qualitative influence on the development of string music that far exceeded its quantitative parameters. In only six volumes of instrumental pieces Corelli set forth models of two kinds of trio sonatas, two kinds of solo sonatas, and two kinds of concerti grossi. The two kinds were works cast in either (1) the slow-fast-slow-fast pattern of movements long associated with sonatas used within the Catholic liturgy, or (2) the allemande-corrente-sarabande-gigue pattern popular in suites associated with secular occasions, especially balli to celebrate weddings, investitures, and the rites of passage. These types became known respectively as "church" (da chiesa) and "chamber" (da camera) sonatas or concertos.

Born in Fusignano in 1653, Corelli developed exceptional skills and an impeccable sense of current taste. His foundation as a musician was formed primarily in Bologna. He appeared in Rome before the end of the 1670s, but his whereabouts over the next few years are hazy and much disputed. Claims that he visited Paris and the courts of Hanover and Munich cannot be substantiated. The dedicatees of his printed works form a clear guide to his most ardent patrons. Rome, with its wide assortment of churches, cardinals' palaces, and unusual cultural enclaves, such as the court-in-exile of Queen Christina of Sweden, offered much to keep a violinist of Corelli's caliber musically engaged.

When viewed in the context of the composer's identified patrons, it becomes clear that Corelli's even-handed attention to both church and chamber genres represented a conscious effort to satisfy both cardinals and princes. The immense reach of Corelli's music far into the eighteenth century demonstrates its universal appeal. Printed copies of his works from that time are widely spread throughout Europe, North America, and East Asia. This appeal can now be extended through the use of tools to make it instantly playable and viewable in score as well as to visualize those features that clarify what the essence of its appeal was and is.

Church and Chamber Sonatas Opp.1-4

The first four of Corelli’s volumes contain “trio” sonatas—sonatas for two violins and basso continuo. In the case of the “church” sonatas (sonate da chiesa; Opp. 1 [1681] and 3 [1689]), the works were usually accompanied by organ, which would be reinforced by a cello or a lute or both. In contrast, “chamber” sonatas (sonate da camera, Opp. 2 [1685] and 4 [1692]) were accompanied by harpsichord, often reinforced by cello.

In church sonatas, imitative writing could occur between treble and bass instruments or between the two violins. Chamber sonatas contained a more variable number of movements, each of which employed the meter of a particular dance type. In addition to the Allemande (a fast movement in duple meter with flowing sixteenth notes), Sarabande (a slow dance in triple meter), Corrente (a “running” or moderately fast dance in triple meter), and Gigue (a fast movement in compound meter, such as 12/8), several other movement types could occur.

Although the typologies were inspired by real-world differences of social function, the meanings of the terms, and of the musical prototypes, drifted from these idealized norms to suit special situations and fickle tastes. They necessarily accommodated the styles of individual composers. It was Corelli’s Op. 2 that seems to have established a foothold for the practical use of the term sonata da camera. The careful distinction between church and chamber styles may have had more of a social-intellectual impetus in Rome than it would have elsewhere. Several cardinals of the late seventeenth century maintained their own musical staffs. Music suitable for enhancing the Elevation of the Host at mass had a very specific use and demanded taste that was not extravagant, while music for the chambers of the aristocracy could invite bodily movement and summon the meters and rhythmic patterns of dances. Op. 4 had the special qualification (title-page) of being intended for the accedmia, or learned gathering, in the palace of Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni.

Had he never composed his solo sonatas or concerti grossi, Corelli’s music would still have left an enormous imprint on European musical culture of his time and the ensuing decades. Up to the end of the seventeenth century, Op. 1 was reprinted 11 times; Op. 2, 12 times; Op. 3, 8 times; and Op. 4, 6 times, in all cases in Italy. Counting eighteenth-century and foreign reprints, the numbers rise to totals of 39, 41, 31, and 39, amounting to a total of 148 printed editions of the sonatas. No other composer of his generation achieved this kind of recognition. These numerous editions pervaded every corner of Europe and the North American colonies. They were models for countless violinists and composers throughout the eighteenth century.

Why did Corelli’s trio sonatas have such a broad appeal? For listeners, the works achieved a happy balance between articulate detail and simplicity of melodic line; between imitative interactions between instruments and simple homophony; between clarity of line and subtlety of ornamentation; and between familiar rhythmic templates and momentary deviations from them.

Editions were bought, however, by those wishing to perform the works. Here Corelli benefited from coincidences of time and place. Corelli’s works were optimally available to the rapidly growing number of amateur players that enjoyed playing bowed string instruments. The works were rewarding without being impossibly difficult. Corelli’s own skill as a performer was demonstrated before some of the most astute and musically able audiences of the time. His concerts for Arcadian gatherings organized for the court-in-exile of Queen Christina of Sweden on the slopes of the Janiculum fed legends that lived on long after the composer, and the Arcadian Academy, were dead. Finally, Corelli’s trio sonatas anticipated the musical values that would later become core features of what we now call “classical music.”

Opp. 1-4 PDF scores

Opp. 1-4 MIDI files by movement

| Sonate da chiesa, Op. 1 | Sonate da camera, Op. 2 | Sonate da chiesa, Op. 3 | Sonate da camera, Op. 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. 1: 1, 2, 3, 4 | No. 1: 1, 2, 3, 4 | ||

| No. 2: 1, 2, 3, 4 | No. 2: 1, 2, 3 | ||

| No. 3: 1, 2, 3 | No. 3: 1, 2, 3, 4 | ||

| No. 4: 1, 2, 3, 4 | No. 4: 1, 2, 3, 4 | ||

| No. 5: 1, 2, 3, 4 | No. 5: 1, 2, 3, 4 | ||

| No. 6: 1, 2, 3, 4 | No. 6: 1, 2, 3 | ||

| No. 7: 1, 2, 3 | No. 7: 1, 2, 3, 4 | ||

| No. 8: 1, 2, 3, 4 | No. 8: 1, 2, 3, 4 | ||

| No. 9: 1, 2, 3, 4 | No. 9: 1, 2, 3 | ||

| No.10: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | No.10: 1, 2, 3 | ||

| No.11: 1, 2, 3, 4 | No.11: 1, 2, 3 | ||

| No.12: 1, 2, 3, 4 | No.12: 1 (Ciacona) |

Arrangements of Corelli sonatas

Geminiani's concerti grossi based on Corelli sonatas

Francesco Geminiani published a set of six concerti grossi based on selected sonatas from John Walsh's edition [#569] of Corelli's sonatas (London, 1735). The overt relationship between Geminiani's concertos and Corelli's sonatas is indicated in the table:

| Composer | Arranger genre | Corelli genre | Corelli ID | Arranger source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geminiani | Concerto grosso | Sonata da chiesa | Op. 3, n. 1 | Walsh #569 |

| Geminiani | Concerto grosso | Sonata da chiesa | Op. 3, n. 3 | Walsh #569 |

| Geminiani | Concerto grosso | Sonata da chiesa | Op. 3, n. 4 | Walsh #569 |

| Geminiani | Concerto grosso | Sonata da chiesa | Op. 3, n. 9 | Walsh #569 |

| Geminiani | Concerto grosso | Sonata da chiesa | Op 3, n. 10 | Walsh #569 |

| Geminiani | Concerto grosso | Sonata da chiesa | Op. 1, n. 9 | Walsh #569 |

Geminiani had earlier transcribed as concerti grossi Corelli's solo sonatas Op. 5, nn. 1-6 (1726) and nn. 7-12 (1729). Opp. 5 and 6 were also arranged in various ways and sometimes anonymously through the 1780s by several others, mainly in England and Germany.

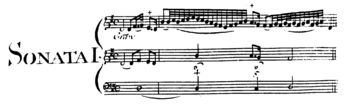

(Solo) Violin Sonatas Op. 5

Because of their exquisite balance of features, trio sonatas offered little opportunity for the virtuoso display that was rising to prominence as the seventeenth century ended. We can be sure that accolades of Corelli’s playing were not generated by his contributions to restraint so much as they were by the reputation he gained as a star (at times even a demonically "possessed") performer. It is in his famous violin sonatas of Op. 5 that his gifts for eloquence find their clearest expression. Corelli dedicated the volume on January 1, 1700, and some now claim that he wished consciously to address his works to the new century.

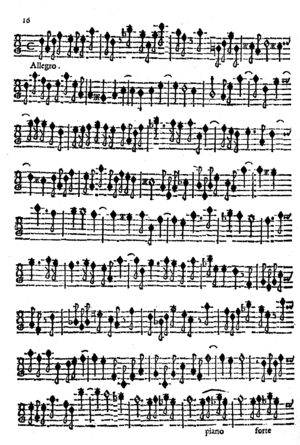

The first six works are sonate da chiesa of five movements. Most of the movements are fast. Not uncommonly, the first movement is marked Vivace, the fifth a mere Allegro. The second six sonatas are da camera, with allemandes, sarabandes, gavottes, and/or gigues predominating after an opening Preludio. Nos. 7-9 are composed in four movements, Nos. 10 and 11 in five. The final work is a set of vigorous variations over the Folìa bass. In contrast to all the trio sonatas, the violin sonatas of Op. 5 are aimed at players of distinction. They offer great scope for virtuosity and individual interpretation. Several contain passages dominated by long sequences of multiple stops or polyphonic voicing.

In contrast to the four volumes of trio sonatas, which were published many times over in Rome, Bologna, and Modena, the solo sonatas had a more discreet entry into the world. The first printing was a private one (Bologna) for Sophie Charlotte, the Electress of Brandenburg. No consistent rendering of the opus enjoyed wide printed circulation, but the diffusion of manuscript copies with individual realizations of popular passages was considerable. Writing ornamented versions of the violinist's part in the slow movements of Op. 5 became an intellectual sport for skilled performers in the eighteenth century.

Debate continues on the range of intents behind these efforts, for some examples preserve the essential melodic lines of Corelli's originals, while others strike off independently and morph into movements of significantly altered content. The question of whether the variations on the first six works, attributed to Corelli in an appendix to a 1710 Dutch reprint of Op. 5, are really by him remains open because of an absence of direct evidence.

Collectively, the many ornamented versions document how greatly individual realizations varied and how elaborate performance practice became in the eighteenth century. Musicologist Neal Zaslaw, who considers Corelli's authorship of the 1710 elaborations probable, suggests that the highly ornamented versions of the next century would sometimes have required a reduced tempo--simply to accommodate all the notes. Apart from the gymnastics that his slow movements elicited in later arrangements, Corelli provides plenty of models for his kind of virtuosity in the fast movements of the original print.

Note about performing Corelli's Op. 5

Op. 5 PDF scores

The Concerti grossi Op. 6

In today's repertory, the Corelli's Concerti grossi Op. 6 are regarded as the culminating works of their genre, which had a relatively short shelf-life but which exerted a strong impact on the future direction of ensemble music for strings. Corelli signed the dedication for Op. 6 in Rome on 3 December 1712, five weeks before his death. The two volumes did not appear until 1714.

As a genre, the concerto grosso was a logical outgrowth of the trio sonata. The evolution came about in stages. The differentiation of a concertino (group of soloists) from a ripieno had been found abundantly in the early years of the seventeenth century. The difference would be expressed in written notation by clustering like-timbred instruments (as in modern scores). This clarified the on-again, off-again nature of collaboration between the groups.

The concerto grosso was both more economical and more articulate. It was economical in extracting all the concertino parts from the ripieno parts. There was no musical independence between the groups. In performance, however, the ripieno sounded fuller not only when it involved more instruments but also because a part for viola(s) was added to the two violins and string bass (or cello). Alternation between soli and tutti became more purposeful, ripieno refrains (ritornelli) became the norm, and the overall structure of the work was architecturally clear rather than, as in earlier decades, somewhat meandering.

The viola parts in Corelli’s Op. 6 are particularly of interest. They do not occur in any of his other published works, but they show him to be devoted to enabling the instrument to be a full musical participant. (Viola parts in earlier and later times could be entirely perfunctory.)

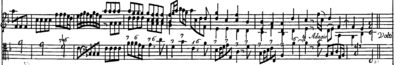

Beyond the considerations of resulting sonority, Corelli provides some highly elaborated movements in both sections of Op. 6. The first eight works are modeled on the sonata da chiesa, the "church" sonata. They have numerous changes of tempo but few extensive slow movements. Adagio and Largo passages are inclined to be short and transitional. The last four works are modeled on the sonata da camera, the "chamber" sonata. Most employ suite movements such as allemandes, sarabandes, correntes, and gigues. They do not employ the fussy tempo contrasts (allegro, adagio, et al.) of the first eight works.

The long-time favorite of Op. 6 has been the Christmas Concerto (No. 8, fatto per la notte di Natale, made for Christmas night). The 6/8 meter and the drone bass were widely associated with the simple music of shepherds, who carried in from the hills a rustic species of bagpipe (zampogna) that played in parallel thirds over a drone.

Op. 6 PDF scores

Accompaniment styles in Corelli’s works

Relatively little about Corelli’s music is controversial, but discussions about exactly how it should be accompanied continue. Note the differences in designating bass and basso continuo in the printed collections in the following table (instrument names in parentheses indicate the lack of an independent part).

| Opus/Title | Bass instrument | Basso continuo | Partbooks | Dedicatee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Sonate a tre (Rome, 1681) | Violone o arcileuto | Basso per l’organo | Due Violini, Violone o Arcileuto, Organo | Christina Alexandra, Queen of Sweden |

| 2: Sonate da camera a tre (Rome, 1685) | Violone o cimbalo | Violone o cimbalo | Due Violini, Violone o Cembalo | Benedetto Pamphili, cardinal |

| 3: Sonate a tre (Rome, 1689) | Violone o arcileuto | Basso per l’organo | Due Violini, Violone o Arcileuto, Organo | Francesco II d’Este, duke of Modena |

| 4: Suonate da camera (Rome, 1694) | Violoncello e cembalo | Violoncello e cembalo | Due Violini, Violone o Cembalo | Academy of Pietro Ottoboni, cardinal |

| 5: Sonate a violino (privately printed, 1700) | Violone o cembalo | Violone o cembalo | Score: Violino e Violone o Cembalo | Sophie Charlotte, electress of Brandenburg |

| 6: Concerti grossi (op. post., 1714) | Violoncello di concertino; basso di concerto grosso ad arbitrio (che si possono raddopiare) | ** | Due Violini e Violoncello di concertino; Altri Violini, Viola, e Basso di concerto grosso | Johann Wilhelm, Prince Palatine, Duke of Bavaria |

Although substantial liberty was accorded performers in matters of accompaniment, Corelli’s published music shows a clear distinction between two continuo practices: (1) organo with violone (double bass or other bowed string instrument in bass range) or theorbo (archlute), or (2) the choice of violone or harpsichord. This divergence separates the “church” and “chamber” collections substantially.

**In the Concerti grossi Op. 6 Corelli provides figured bass parts for both the Violoncello di concertino and for the unspecified Basso del Concerto grosso. As Friedrich Chrysander pointed out more than a century ago, the figuration implies the likelihood that a keyboard (or theorbo) was available to both the concertino and the ripieno groups, even though neither is specifically mentioned in the partbooks. In Corelli's time the choices for Op. 6 would have been influenced by the "church" or "chamber" nature of the specific work.

Unpublished works by Corelli

Although substantial evidence suggests that Corelli's works were much played and highly polished by the time they appeared in print, one sinfonia and a few trio sonatas in manuscript have been identified in recent decades. Many dozens more have been linked to another composer (e.g. G. B. Lulier, G. Ph. Telemann) or consigned to the status of dubious authenticity.

Further information

Hans Joachim Marx's critical catalog of Corelli' works (Die Überlieferung der Werke Arcangelo Corellis. Catalogue raisonné (Arcangelo Corelli. Historisch-kritische Gesamtausgabe der musikalischen Werke, Suppl.), Cologne: Arno Volk Verlag, 1980) itemizes primary sources for these works. Their spread from Corelli's death to the time of Beethoven brought with it numerous modifications and elaborations. The number of movements may vary from one edition to another. Individual movements, especially galliards in the sonatas, also migrated from work to work.

For further details about individual works, the best tool is the online RISM catalog, which gives extensive coverage to the explosion in Corelli copies in the eighteenth century. In contrast to the 48 trio sonatas presented here, RISM (2024) lists 1,258 instances across these many copies and arrangements.

2010, 2021, 2024 Eleanor Selfridge-Field, commentary. Encoding and edition by Edmund Correia, Jr., and Frances Bennion. Rendering and web development, incorporating software developed by Walter B. Hewlett, by Craig Stuart Sapp.

The short URL for this page is https://corelli.ccarh.org