Difference between revisions of "MuseData: Antonio Vivaldi"

| (132 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

===Op. 1: <i>Suonate da camera a trè, due violini e violone o cembalo</i>=== | ===Op. 1: <i>Suonate da camera a trè, due violini e violone o cembalo</i>=== | ||

| − | Vivaldi's twelve sonatas Op. 1 are presumed to have been published prior to his appointment as <i>maestro di violino</i> at the Ospedale della Pietà, Venice, because he is described without reference to the institution as "<i>musico di violino, professore veneto</i>" (a violinist and teacher in the Veneto). | + | Vivaldi's twelve sonatas Op. 1 are presumed to have been published prior to his appointment as <i>maestro di violino</i> at the Ospedale della Pietà, Venice, because he is described without reference to the institution as "<i>musico di violino, professore veneto</i>" (a violinist and teacher in the Veneto). The works were dedicated to the count Annibale Gambara, one of five sons in a big family of noblemen from [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brescia Brescia] (the city in which Vivaldi's father was born), a provincial capital in the western Veneto. The Gambara had a modest palace on the Grand Canal in the Venetian parish of San Barnabà. |

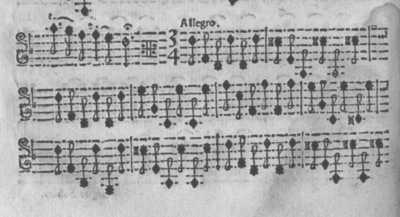

| − | [[File:Op1-12_Folia_V1.png|400px|thumb|center|Excerpt from the Violino primo (first violin) part of the Folìa of Vivaldi's Sonata Op. 1, No. 12 (Venice: Giuseppe Sala, 1705). | + | [[File:Op1-12_Folia_V1.png|400px|thumb|center|Excerpt from the Violino primo (first violin) part of the Folìa of Vivaldi's Sonata Op. 1, No. 12 (Venice: Giuseppe Sala, 1705). Image from the partbook in the Conservatorio Benedetto Marcello, Venice. Used by permission.]] |

| − | These trio sonatas contained various numbers of movements (3 to 6), most in binary form. The four outer works (Nos. 1, 2, 11, and 12) | + | These trio sonatas contained various numbers of movements (3 to 6), most in binary form. The four outer works (Nos. 1, 2, 11, and 12) are in minor keys, the others in major ones. The best known work is Op. 1, No. 12, an ambitious set of variations on the <i>folìa</i>. Vivaldi may have been inspired by [http://scores.ccarh.org/corelli/op5/corelli-op5n12.pdf Arcangelo Corelli]'s set of Folìa variations [http://scores.ccarh.org/corelli/op5/corelli-op5n12.pdf Op. 5, No. 12] (1700), but the trio texture changes the dynamics of the realization substantially. |

| + | |||

| + | The earliest surviving print of Op. 1 was published in Venice (G. Sala) in 1705. Only fragments of it survive today in the library of the "Benedetto Marcello" Conservatory in Venice. (Scholars suspect that the music predated Vivaldi's appointment at the Ospedale of the Pietà, it is not mentioned in the title-page of Op. 1.) Vivaldi's collection was reprinted in Amsterdam in 1723 (E. Roger, as print No. 363), in Paris in 1759 (Le Clerc), and in Austria in 1759. Many movements are brief and musically simple, so much so that were one to judge from this opus alone, one would not have anticipated the kind of success that Vivaldi later found. [https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ESCaqRIJReiXkotziSUcIMfeihKXZWQb2_w-xs_GhFU/edit#gid=0 Critical notes for Vivaldi's Op. 1.] | ||

{{VivaldiOp1PDF}} | {{VivaldiOp1PDF}} | ||

===Op. 2: <i>Sonate a violino e basso per il cembalo</i>=== | ===Op. 2: <i>Sonate a violino e basso per il cembalo</i>=== | ||

| + | |||

[[File:Carlevaris_FredIV_viaGetty-Google.png|575px|thumb|left|Detail of Luca Carlevaris's depiction of the regatta held on the Grand Canal, Venice, for Frederick IV of Denmark (1709). Reproduction of public-domain image from the Getty Museum as shown in the Google Art project.]] | [[File:Carlevaris_FredIV_viaGetty-Google.png|575px|thumb|left|Detail of Luca Carlevaris's depiction of the regatta held on the Grand Canal, Venice, for Frederick IV of Denmark (1709). Reproduction of public-domain image from the Getty Museum as shown in the Google Art project.]] | ||

| − | The trio sonata, over which Vivaldi had exhibited his command in Op. 1, had been the most prevalent instrumental genre of the 1690s, but in the first decade of the eighteenth century interest began to gravitate towards the "solo" sonata--a work in several movements one ensemble instrument and a basso continuo. In this 1709 collection by the Venetian publisher Antonio Bortoli Vivaldi pursued a more expressive vein of musical enticement. The opus was dedicated to the visiting young monarch Frederick IV of Denmark. As prince of Schleswig Holstein, his extended stay drew much artistic attention. No fewer | + | The trio sonata, over which Vivaldi had exhibited his command in Op. 1, had been the most prevalent instrumental genre of the 1690s, but in the first decade of the eighteenth century interest began to gravitate towards the "solo" sonata--a work in several movements for one ensemble instrument and a basso continuo. In this 1709 collection by the Venetian publisher Antonio Bortoli, Vivaldi pursued a more expressive vein of musical enticement. The opus was dedicated to the visiting young monarch Frederick IV of Denmark. As prince of Schleswig-Holstein, his extended stay drew much artistic attention. No fewer than three operas were dedicated to him. |

| − | Seven of these sonatas were cast in minor keys. The movement structure remained variable. | + | Seven of these sonatas were cast in minor keys. (An asterisk (*) indicates a transcription using the key signature of the original print, while ** indicates a modernized key signature.) The movement structure of these early prints remained variable. Vivaldi was moving in the direction of fewer movements but in coincidence we find greater musical elaboration within longer movement. The composer was now described as a <i>maestro dei concerti</i> (concertmaster) of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ospedale_della_Piet%C3%A0 Ospedale della Pietà]. |

{{VivaldiOp2PDF}} | {{VivaldiOp2PDF}} | ||

| − | Like Op. 1, Op. 2 had a long | + | Like Op. 1, Op. 2 had a long afterlife in both reprints and manuscript copies, mainly abroad. These included the publications of E. Roger (Amsterdam, 1712) and several editions (1721-1730) by I. Walsh and J. Young (London). [Critical notes for Vivaldi's Op. 2.] |

===Op. 3: <i>L'estro armonico: Concerti</i>=== | ===Op. 3: <i>L'estro armonico: Concerti</i>=== | ||

| − | [[File:Ferdinando_de'_Medici_c1687_Cassana.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Portrait of Ferdinando de' Medici, grand prince of Tuscany, in c | + | [[File:Ferdinando_de'_Medici_c1687_Cassana.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Portrait of Ferdinando de' Medici, grand prince of Tuscany, in <i>c</i>1687 by the Venetian painter Niccolò Cassana. Wikimedia Commons.]] |

| − | The first concertos by Vivaldi to reach print were those of Opus 3 (Amsterdam, 1711). With them Vivaldi suddenly became a celebrity, for although he was well known as a virtuoso, his previously published works had found a relatively modest reception. Vivaldi's titles remained as they were in Op. 2. Most composers described the contents of a publication in sufficient detail to indicate instrumentation, but Vivaldi settled for the word "Concerti" in order to allow space for the titles of his patron, the Grand Prince of Tuscany, [http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinando_de%27_Medici#Teatro Ferdinando III (1663-1713)]. The Grand Prince, who led a flamboyant life, enjoyed his visits to Venice, where however he contracted syphilis in 1696. This led to his premature death and changed the course of Tuscan (and imperial) history. Meanwhile, however, his patronage of music benefited many composers of the time including [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomaso_Albinoni Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1751)], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Handel George | + | The first concertos by Vivaldi to reach print were those of Opus 3 (Amsterdam, 1711). With them Vivaldi suddenly became a celebrity, for although he was well known as a virtuoso, his previously published works had found a relatively modest reception. Vivaldi's titles remained as they were in Op. 2. Most composers described the contents of a publication in sufficient detail to indicate instrumentation, but Vivaldi settled for the word "Concerti" in order to allow space for the titles of his patron, the Grand Prince of Tuscany, [http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinando_de%27_Medici#Teatro Ferdinando III (1663-1713)]. The Grand Prince, who led a flamboyant life, enjoyed his visits to Venice, where however he contracted syphilis in 1696. This led to his premature death and changed the course of Tuscan (and imperial) history. Meanwhile, however, his patronage of music benefited many composers of the time including [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomaso_Albinoni Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1751)], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Handel George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)], and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alessandro_Scarlatti Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725)]. His Bavarian wife, [http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Violante_Beatrice_di_Baviera Violante Beatrice (1673-1731)], was in many ways a still more significant supporter of individual singers and instrumentalists. |

| − | Having now completed eight years | + | Having now completed eight years of teaching at the [[Ospedale of the Pietà]] in Venice, Vivaldi shows himself to have experimented with a variety of approaches to textures and groupings of instruments. These twelve works are arranged cyclically, such that Nos. 1, 4, 7, and 10 are scored for four violins and string orchestra; Nos. 2, 5, 8, and 11 for two violins, violoncello, and string orchestra; and Nos. 3, 6, 9, and 12 for solo violin (Violino Principale) and string orchestra. Within the <i>concertino</i> groups (four violins or, alternatively, two violins and violoncello), there is further separation. The "four violins" model often involves the pairing of the instruments such that one duo imitates another. This kind of experimentation is suggested by the word <i>estro</i>, which refers to gestational properties whereby one musical passage generates the need for the next. In musical terms, the sophistication of the idea represented an enormous step forward for Vivaldi, whose first sonatas were primitive and somewhat generic by comparison. |

| − | Additionally, the music was more cogent than before, the organization manifestly rational. The imaginative scoring, careful markup, and newly pungent musical | + | Additionally, the music was more cogent than before, the organization manifestly rational. The imaginative scoring, careful markup, and newly pungent musical effects were novelties not found in Opp. 1 or 2. If he had leaned on the familiar models of [http://wiki.ccarh.org/wiki/MuseData:_Arcangelo_Corelli Arcangelo Corelli (1753-1713)] before, Vivaldi was now producing music that was novel, ambitious, and aesthetically pleasing. Largely in coincidence with this publication, Vivaldi's concerts at the Pietà began to win plaudits from a succession of visiting dignitaries from abroad. |

Within the context of the early concerto, Op. 3 was equally noteworthy. The now elderly Corelli had perfected the <i>concerto grosso</i> [his [http://wiki.ccarh.org/wiki/MuseData:_Arcangelo_Corelli#The_Concerti_grossi_Op._6 Op. 6] would be published only posthumously in 1714]. Vivaldi's concertos for two and four violins had some debts to these works, but his concertos for solo violin and orchestra did not have Corellian models to follow. The trumpet concertos by [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alessandro_Scarlatti Giuseppe Torelli (1658-1709)] are an oft mentioned alternative model, but Vivaldi's skills at articulation and exhibitionism were unrivaled. The violin was capable of much greater subtlety than the trumpet. | Within the context of the early concerto, Op. 3 was equally noteworthy. The now elderly Corelli had perfected the <i>concerto grosso</i> [his [http://wiki.ccarh.org/wiki/MuseData:_Arcangelo_Corelli#The_Concerti_grossi_Op._6 Op. 6] would be published only posthumously in 1714]. Vivaldi's concertos for two and four violins had some debts to these works, but his concertos for solo violin and orchestra did not have Corellian models to follow. The trumpet concertos by [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alessandro_Scarlatti Giuseppe Torelli (1658-1709)] are an oft mentioned alternative model, but Vivaldi's skills at articulation and exhibitionism were unrivaled. The violin was capable of much greater subtlety than the trumpet. | ||

====Dissemination of Individual Works from Op. 3==== | ====Dissemination of Individual Works from Op. 3==== | ||

| − | The <i>Concerti</i> Op. 3 were so popular that the entire opus was reprinted in Amsterdam within a year. Other reprints followed in both London and Paris through 1751. Because of the cyclical rotation of different combinations of instruments from work to work individual pieces in Op. 3 led themselves to diverse uses. The basic organization is shown in the table. Parsed one way, it is a four-fold cycle of three works. The textures vary with the instrumentation. | + | The <i>Concerti</i> Op. 3 were so popular that the entire opus was reprinted in Amsterdam within a year. Other reprints followed in both London and Paris through 1751. Because of the cyclical rotation of different combinations of instruments from work to work, individual pieces in Op. 3 led themselves to diverse uses. The basic organization is shown in the table. Parsed one way, it is a four-fold cycle of three works. The textures vary with the instrumentation. |

| − | Several works from Opus 3 took on lives of their own. Six works (indicated by an asterisk*) were transcribed by J. S. Bach, and there are faint clues that Bach may have transcribed them all. | + | Several works from Opus 3 took on lives of their own. Six works (indicated by an asterisk*) were transcribed by J. S. Bach, and there are faint clues that Bach may have transcribed them all. Bach was highly sensitive to the cyclical instrumentation of Vivaldi's collection: Nos 1, 4, 7, and 10 were set for two pairs of solo violins; Nos. 2, 5, 8, and 11 for a trio of soloists (two violins and violoncello); Nos. 3, 6, 9, and 12 for principal violin, in all cases with string orchestra. As the table below shows, Bach chose the second type for an organ adaptation and the third type for concertos for harpsichord and strings, while the first type served as a model for his lone concerto for four harpsichords and strings. The trio sonata, which was at its peak in the years 1700-1710, was a popular reservoir for organ transcriptions in Germany, but the other adaptations had no such currency. Concertos for four harpsichords were unknown. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Wide circulation of Vivaldi's concertos was further stimulated by John Walsh's edition of Op. 3 in <i>c.</i> 1715. In this print, the order of Nos. 6-9 was altered so that these concertos became Nos. 8, 9, 6, and 7. The clavichord transcriptions of Anne Dawson include many works in Vivaldi's Opp. 3 and 4 and show a further dimension of the music's adaptation. Numerous transcriptions and copies survive in Europe and North America. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====CCARH Scores and Parts for Opus 3==== | ====CCARH Scores and Parts for Opus 3==== | ||

| − | [[File:Op3DoverCover.jpg|||left]] | + | [[File:Op3DoverCover.jpg|100px||left]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The collection | + | CCARH cooperated with Dover Publications Inc. in producing the scores that appear in <i>L'estro armonico: Twelve Concertos for Violins and String Orchestra, Op. 3</i>. The cover is shown below. The collection entitled <i>L'estro armonico</i> was the first title under Vivaldi's name to draw widespread attention. It is likely that some of the works had already been performed in selected gatherings. They were profusely copied, arranged, and reprinted (with numerous variants) over the next few decades. This edition is based primarily on the prints of Etienne Roger Nos. 50 (containing parts for Nos. 1-6) and 51 (Nos 7-12; 1711) in conjunction with several manuscript sources for specific works. |

| − | + | For bound paper copies, see Vivaldi, Antonio. <i>"L'Estro armonico", Op. 3 in Full Score: 12 Concertos for Violins and String Orchestra</i>, ed. Eleanor Selfridge-Field (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications; 1999). Available from Amazon [http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0486406318/themefinder/002-2800507-6138416 ISBN 0-486-40631-8] and Dover [http://store.doverpublications.com/review.html?pr_page_id=0486406318 ISBN 0-486-40631-8]. | |

| − | For bound paper copies, see Vivaldi, Antonio. <i>"L'Estro armonico", Op. 3 in Full Score: 12 Concertos | ||

| − | for Violins and String Orchestra</i>, | ||

| − | |||

| − | [http://store.doverpublications.com/review.html?pr_page_id=0486406318 ISBN 0-486-40631-8 | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

{{VivaldiOp3PDF}} | {{VivaldiOp3PDF}} | ||

| − | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

| + | The Dawson transcriptions for Nos. 5, 7, 8, and 12 as a group are available [http://scores.ccarh.org/vivaldi/op3dawsonnew/ here]. | ||

===Op. 4: <i>La Stravaganza: Concerti in six parts</i>=== | ===Op. 4: <i>La Stravaganza: Concerti in six parts</i>=== | ||

| − | Vivaldi's violin concertos Op. 4 (announced in London on January 1, 1715) achieved a much broader penetration of the European market than any previous publication of his music. The collection, published in Amsterdam as Estienne Roger's prints Nos. 399 and 400, bore the title <i>La Stravaganza</i> (The Extravaganza), a designation popular at the time. In musical contexts it usually referred to chromatic harmonies, but in Vivaldi's case it forewarned prospective players of the challenges posed, | + | Vivaldi's violin concertos Op. 4 (announced in London on January 1, 1715) achieved a much broader penetration of the European market than any previous publication of his music. The collection, published in Amsterdam as Estienne Roger's prints Nos. 399 and 400, bore the title <i>La Stravaganza</i> (The Extravaganza), a designation popular at the time. In musical contexts it usually referred to chromatic harmonies, but in Vivaldi's case it forewarned prospective players of the challenges posed, especially for the principal violinist. (Up to this time, Roger had principally offered trio sonatas and <i>concerti grossi</i>, which were less demanding.) |

Op. 4 was a compendium of virtuoso techniques that were popularized by Vivaldi, who, as a performer, was known far and wide for his daring. His near-peers in this regard were violinist-composers such as Tomaso Albinoni and Lodovico Madonis, but their most demanding works appeared some years later and were less widely distributed. Op. 4 was dedicated to a Venetian nobleman, Vettor Delfin, whose family were largely engaged in military affairs. With only one exception (Op. 4, No. 7), the concertos were written in three movements. | Op. 4 was a compendium of virtuoso techniques that were popularized by Vivaldi, who, as a performer, was known far and wide for his daring. His near-peers in this regard were violinist-composers such as Tomaso Albinoni and Lodovico Madonis, but their most demanding works appeared some years later and were less widely distributed. Op. 4 was dedicated to a Venetian nobleman, Vettor Delfin, whose family were largely engaged in military affairs. With only one exception (Op. 4, No. 7), the concertos were written in three movements. | ||

| − | At the time Op. 4 appeared, Vivaldi had been filling holes left by the departure of [http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francesco_Gasparini Francesco Gasparini (1661-1727)] at the Pietà. | + | At the time Op. 4 appeared, Vivaldi had been filling holes left by the departure of [http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francesco_Gasparini Francesco Gasparini (1661-1727)] at the Pietà. He was now turning his attention to motets and oratorios <i>per force</i> to bridge the gap left by Gasparini. It is therefore likely that most of these pieces were composed before the elder <i>maestro</i>'s departure. Reprints of Op. 4 appeared in 1723, 1728, and 1730, but selected individual works enjoyed independent circulation. Vivaldi had now reached the point where demand for his instrumental music exceeded the amount of time he could afford to devote to them. It may be for this reason that echoes of Op. 4 appear in a few later works by Vivaldi. Op. 7, No. 1, for example, was a first cousin of Op. 4, No. 9; myriad other variants of this set were quoted in later works. The cumulative effect was a splintering of work-identities that still confuses musicians today. Vivaldi himself adapted many of his works to suit new purposes as appropriate occasions arose. [https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ESCaqRIJReiXkotziSUcIMfeihKXZWQb2_w-xs_GhFU/edit#gid=1955277646 Critical notes for Op. 4.] |

{{VivaldiOp4PDF}} | {{VivaldiOp4PDF}} | ||

| − | ===Op. 5: <i>VI Sonate/ | + | ===Op. 5: <i>VI Sonate/quattro à violino solo e basso e due a due violini e basso continuo</i>=== |

| − | Four of the six sonatas of Op. 5, published in Amsterdam (1716) as | + | Four of the six sonatas of Op. 5, published in Amsterdam (1716) as Jeanne Roger's print No. 418, were remainders of Vivaldi's Op. 2, an opus consisting of a dozen solo violin sonatas. These works appeared with the added information |

| + | <i>O vero Parte Seconda del Opera Seconda</i>". During the visit of the young Danish king Frederick Christian IV to Venice in the winter of 1709, a great many banquets and balls were planned. Easily half of them were canceled either by hosts or guests because many people (including the doge and one of the Venetian Republic's official hosts) died. No autograph material for this opus survives. Op. 2 had been dedicated to Frederick Christian, but Op. 5, containing a mixed repertory, was an orphan of sorts. It lacked a dedicatee, although an edition by M.C. Le Cène was brought out in <i>c</i>1723. Although few works were copied in manuscript, an exception was the first movement of Op. 5, No. 6, which was included in J. B. Cartier's <i>L'Art du Violon</i> (Paris, 1798). | ||

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! Opus, Work No. !! Ryom No. !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Score | + | ! Opus, Work No. !! Ryom No. !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Score (Roger) !! Score (Le Cène) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 5, No. 1 || RV 18 || Sonata / V, | + | | Op. 5, No. 1 [Op. 2, No. 13] || RV 18 || Sonata / V, Bc || F Major || Example || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 5, No. 2 || RV 30 || Sonata / V, | + | | Op. 5, No. 2 [Op. 2, No. 14] || RV 30 || Sonata / V, Bc || A Major || Example || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 5, No. 3 || RV 33 || Sonata / V, | + | | Op. 5, No. 3 [Op. 2, No. 15] || RV 33 || Sonata / V, Bc || B{{music|flat}} Major || Example || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 5, No. 4 || RV 35 || Sonata / V, | + | | Op. 5, No. 4 [Op. 2, No. 16] || RV 35 || Sonata / V, Bc || B Minor || Example || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 5, No. 5 || RV 76 || Sonata / V1, V2, | + | | Op. 5, No. 5 [Op. 2, No. 17] || RV 76 || Sonata / V1, V2, Bc || B{{music|flat}} Major || Example || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 5, No. 6 || RV 72 || Sonata / V1, V2, | + | | Op. 5, No. 6 [Op. 2, No. 18] || RV 72 || Sonata / V1, V2, Bc || G Minor || Example || Example |

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <i>Critical comments</i>: Despite its thin trail of copies and imitations, the opus is presented in slightly different ways by Jeanne Roger and M.C. Le Cène, although both employ the print number 418. Roger is generous with bowing marks, which bring a certain grace to the music. Yet the Roger lacks continuo figuration, which Le Cène provides generously. These differences in presentation suggest a difference in intended modes of performance--the Roger assuming the use of violin and string bass only, while the Le Cène aims for a keyboard continuo, probably with string bass reinforcement. Le Cène give movement tempo designations (Largo, Allegro, Presto) but excludes the dynamics indications found in Roger. Roger may have allowed for <i>notes inégales</i> in Op. 5, No. 1, for although the dotted patterns are given equivalently in Le Cène, the double dot in the final bar of the Preludio of Roger is an ordinary dot in Le Cène. [https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ESCaqRIJReiXkotziSUcIMfeihKXZWQb2_w-xs_GhFU/edit#gid=911443142 <i>Detailed notes on individual works in both prints</i>] | ||

===Op. 6: <i>VI Concerti à cinque strumenti: 3 violini, alto viola, e basso continuo</i>=== | ===Op. 6: <i>VI Concerti à cinque strumenti: 3 violini, alto viola, e basso continuo</i>=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | Musically, | + | [[File:Op.6n2ii2.png|560px|thumb|left|<small>From Violino principale for second movement of Op. 6, No. 2.</small>]] |

| + | |||

| + | The six concertos for violin and strings of Op. 6, published in Amsterdam in 1716-1717 by Jeanne Roger (as her firm's print No. 452) represent both a continuation and a departure. The instrumental requirements are identical to those of Op. 4: they require a principal violin and a small string orchestra. This short collection could have served as a supplement to Op. 4, given the pattern set by Opp. 2 and 5 (another short set). The absence of a dedicatee and sundry details of the music suggest that Vivaldi did not actively seek this publication and that the print was therefore unauthorized. Mme. Roger heralded Vivaldi's titles as <i>maestro di violino</i> and <i>maestro di concerti</i> at the Pietà. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Musically, four of the six works are in minor keys. Again forming a parallel with Op. 5, it was not followed by myriad other editions, although Le Cène issued one (undated) reprint. | ||

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

| Line 136: | Line 117: | ||

===Op. 7: <i>Concerti a 5 strumenti: Tre violini, alto viola e basso continuo</i>=== | ===Op. 7: <i>Concerti a 5 strumenti: Tre violini, alto viola e basso continuo</i>=== | ||

| − | + | Vivaldi's 12 concertos <i>a 5</i> (three violins, viola, and basso continuo) were, like the works of Op. 6, planned with a <i>violino principale</i> for use in the solo episodes in the outer movements and the middle movement of three-movement works. These two opuses (6 and 7) were the first ones in which <i>all</i> the works contained only three movements. One can see that Vivaldi's idea of the concerto had evolved considerably over a decade. Note, though, that the oboe arrangements of Opp. 7, Nos. 1 and 7, as well as Op. 11, No. 6 (derived from Op. 7, No. 9) are now considered spurious. Three of the other printed works--Op. 7, Nos. 3, 5, and 10--appear in Jeanne Roger's serial prints (Nos. 470, 471, both of 1720) capture variant versions of circulating manuscripts of the time (<i>c</i>1716-1717). | |

| − | As scores passed through more hands and as Vivaldi himself branched out into new modes of musical expression, his | + | As scores for Vivaldi's concertos passed through more hands and as Vivaldi himself branched out into new modes of musical expression, his works began to spawn ever-changing identities. (The Amsterdam print of Op. 7 was not a publication authorized by the composer.) Among these morphing presentations, Op. 7, No. 3 was revised by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Georg_Pisendel Johann Pisendel] (cf. RV 370), who played a significant role in performing and preserving Vivaldi's music in the Dresden <i>Hofkapelle</i>. No. 9 found a new life in a version for oboe and strings (RV 460), published as Op. 11, No. 6. No. 10 was nicknamed "Il Ritiro" (Withdrawal). No. 11 ("Il Grosso Mogul") was published with a different middle movement (RV 208a) in [https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Dictionary_of_Music_and_Musicians/Walsh,_John Walsh] & Hare's anthology <i>Select Harmony</i> (London, 1730). Many of the works may have been composed considerably earlier than their print dates suggest, and in the case of this pair RV 208 is conjecturally from before 1710, its alternative arrangement from not later than 1720. One manuscript copy of the earlier work includes a written cadenza. It was also transcribed by J. S. Bach for organ as BWV 594. parts and/or scores for five of the works are preserved in early copies in the Sächsische Landesbibliothek, Dresden, while other early versions are found in manuscripts in Manchester (UK) and Trondheim (Norway), among other locations. |

| − | No. 9 found a new life in a version for oboe and strings (RV 460), published as Op. 11, No. 6. No. 10 was nicknamed "Il Ritiro. | ||

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! Opus, No. !! Ryom No. !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Related works !! Score | + | ! Opus, Work No. !! Ryom No. !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Related works !! Score |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 7, No. 1 || RV 465 || Concerto / Ob (VPr) V1 V2 Va Vc Org || B{{music|flat}} Major || | + | | Op. 7, No. 1 || RV 465 || Concerto / Ob (VPr); V1 V2 Va Vc Org || B{{music|flat}} Major || Anh. 143<ref>Works listed in the appendix (<i>Anhang</i>) of Peter Ryom's Vivaldi catalog [RV] are currently considered spurious.</ref> || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| Op. 7, No. 2 || RV 188 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || C Major || || Example | | Op. 7, No. 2 || RV 188 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || C Major || || Example | ||

| Line 157: | Line 137: | ||

| Op. 7, No. 6 || RV 374 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || B{{music|flat}} Major || || Example | | Op. 7, No. 6 || RV 374 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || B{{music|flat}} Major || || Example | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 7, No. 7 || RV 464 || Concerto / Ob (VPr) V1 V2 Va Vc Org || B{{music|flat}} Major || | + | | Op. 7, No. 7 || RV 464 || Concerto / Ob (VPr); V1 V2 Va Vc Org || B{{music|flat}} Major || Anh. 142 || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| Op. 7, No. 8 || RV 299 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || G Major || || Example | | Op. 7, No. 8 || RV 299 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || G Major || || Example | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 7, No. 9 || RV 373 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || B{{music|flat}} Major || || Example | + | | Op. 7, No. 9 || RV 373 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || B{{music|flat}} Major || Anh. 153 || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| Op. 7, No. 10 || RV 294a || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || F Major || RV 294 || Example | | Op. 7, No. 10 || RV 294a || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || F Major || RV 294 || Example | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 7, No. 11 || RV 208a || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || D Major || BWV 594 || Example | + | | Op. 7, No. 11 || RV 208a || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || D Major || BWV 594 (organ) || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| Op. 7, No. 12 || RV 214 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || D Major || || Example | | Op. 7, No. 12 || RV 214 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || D Major || || Example | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Op. 8: <i>Il cimento dell'armonia e dell'invenzione: Concerti a quattro e cinque</i>=== | ===Op. 8: <i>Il cimento dell'armonia e dell'invenzione: Concerti a quattro e cinque</i>=== | ||

| − | Vivaldi's most famous opus was published in Amsterdam by Michel Charles Le Cène in 1725. It is clear, though, that various portions of sundry works had been written earlier. What was perhaps new was the formalization of the scheme, complete with the texts of the sonnets with which they were coordinated, of the first four concertos--The Four Seasons. These works, and their cyclical organization, captured the imagination of many and led to a "Four Seasons" industry of arrangements performances that extends to the current day. | + | Vivaldi's most famous opus was published in Amsterdam by Michel Charles Le Cène in 1725. It is clear, though, that various portions of sundry works had been written earlier. What was perhaps new was the formalization of the scheme, complete with the texts of the sonnets with which they were coordinated, of the first four concertos--The Four Seasons. These works, and their cyclical organization, captured the imagination of many and led to a "Four Seasons" industry of arrangements and performances that extends to the current day. |

| − | Unlike other opuses that postdated Vivaldi's move to Mantua, this one resumed the practice of dedicating the collection to a nobleman, in this case Venceslas, count of Morzin (also Morcin, spelled Marzin in the print itself). | + | Unlike other opuses that postdated Vivaldi's move to Mantua, this one resumed the practice of dedicating the collection to a nobleman, in this case Venceslas, count of Morzin (also Morcin, spelled Marzin in the print itself). Two concertos known only in manuscript, RV 449 and 496, were also dedicated to the count. |

| − | He was Bohemian with townhouses in Prague and Vienna. He was an occasional patron of Venetian opera. Prague, the capital of Bohemia, was a thriving city | + | He was Bohemian with townhouses in Prague and Vienna. He was an occasional patron of Venetian opera. Prague, the capital of Bohemia, was a thriving city with rapidly developing enterprises focused on opera and on the development of string music. One can see how poetic justice prevailed in this dedication: Bohemians not only loved music but were happy to master its component parts. |

| − | This opus was more popular in France than anywhere else. Parisian reprints issued from the presses of Madame Boivin (c. 1739, 1743, 1748). Manuscripts were widely circulated. Rearrangements of portions of the opus were | + | This opus was more popular in France than anywhere else. Parisian reprints issued from the presses of Madame Boivin (c. 1739, 1743, 1748). Manuscripts were widely circulated. Rearrangements of portions of the opus were also proliferated. In Dresden, the orchestration of some works was enriched by Johann Pisendel, who also elaborated some of the articulation. |

| − | In the works as a set, major keys predominate. Nos. 7, 9, | + | In the works as a set, major keys predominate. Nos. 7, 9, and 11 are known in alternative versions. The final of movement of Op. 8, No. 11 presents a particularly complex web of revisions to the alternation of tutti and solo. |

| − | + | ====CCARH Scores and Parts for Op. 8==== | |

| + | The parts for Antonio Vivaldi's Op.8 <i>Concerti</i> accompany the full scores available from Dover Publications: | ||

| + | * Vivaldi, Antonio. "The Four Seasons" and Other Violin Concertos in Full Score; Opus 8, Complete. Ed. by Eleanor Selfridge-Field. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications; 1995. ISBN 0-486-28638-X. | ||

| − | + | The full scores available linked here are generated from the same encoded data but omit editorial details including alternative readings. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<center> | <center> | ||

{{VivaldiOp8PDFTable}} | {{VivaldiOp8PDFTable}} | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| − | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

===Op. 9: <i>La cetra. Concerti</i>=== | ===Op. 9: <i>La cetra. Concerti</i>=== | ||

| − | Vivaldi Concertos Op. 9, published in Amsterdam by Michel Charles Le Cène in Vols. 533 and 534 (datable from 1727), have the distinction of having been dedicated to the emperor Charles VI. The two met two years later in Trieste, where the emperor was more enraptured by Vivaldi's music and the intelligence with which he discussed it than with the diplomatic matters at hand. | + | Vivaldi's Concertos Op. 9, published in Amsterdam by Michel Charles Le Cène in Vols. 533 and 534 (datable from 1727), have the distinction of having been dedicated to the emperor Charles VI. The two met two years later in Trieste, where the emperor was more enraptured by Vivaldi's music and the intelligence with which he discussed it than with the diplomatic matters at hand. Op. 9 is easily confused with a contemporary set of twelve unpublished concertos for violin, also called "La Cetra," that Vivaldi presented to the Emperor during his 1729 visit as part of a diplomatic delegation to Trieste. |

| − | The works of Op. 9 were not so widely circulated as those of other recent volumes of Vivaldi's music, and a few were not new. (Three of the works were known in alternative versions.) The popularity of the "Four Seasons" concertos (Op. 8, Nos. 1-4) blinded the public to Vivaldi's future prints, while Vivaldi's own interest in publishing instrumental music | + | The works of Op. 9 were not so widely circulated as those of other recent volumes of Vivaldi's music, and a few were not new. (Three of the works were known in alternative versions.) The popularity of the "Four Seasons" concertos (Op. 8, Nos. 1-4) blinded the public to Vivaldi's future prints, while Vivaldi's own interest in publishing instrumental music decline after the appearance of this collection. He preferre selling individual manuscripts to well-placed collectors. |

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! Opus, No. !! Ryom No. !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Related works !! Score | + | ! Opus, Work No. !! Ryom No. !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Related works !! Score |

|- | |- | ||

| Op. 9, No. 1 || RV 181a || [VPr]; V1 V2 V3 Va Vc Org || C Major || RV 180 || Example | | Op. 9, No. 1 || RV 181a || [VPr]; V1 V2 V3 Va Vc Org || C Major || RV 180 || Example | ||

| Line 296: | Line 206: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | The part for <i>Violino Principale</i> is lost, although a manuscript part-book for it survives. | + | The part for <i>Violino Principale</i> is lost, although a manuscript part-book for it survives for a few works. |

===Op. 10: <i>VI Concerti a flauto traverso</i>=== | ===Op. 10: <i>VI Concerti a flauto traverso</i>=== | ||

| Line 302: | Line 212: | ||

As published, Vivaldi's Opus 10 is a straightforward collection of concertos for flute and string orchestra. | As published, Vivaldi's Opus 10 is a straightforward collection of concertos for flute and string orchestra. | ||

| − | Most works which originally called for obbligato flutes seem to have originated during the early 1720s, perhaps reflecting opportunities that Vivaldi encountered in Rome, where he stayed intermittently between c | + | Most works which originally called for obbligato flutes seem to have originated during the early 1720s, perhaps reflecting opportunities that Vivaldi encountered in Rome, where he stayed intermittently between <i>c</i>1719 and 1724. Although the transverse flute was then little known in Italy, the availability of an excellent player was essential for the execution his works for it. |

| − | Opus 10 appeared in 1729, in rough coincidence with Vivaldi's violin concertos Opp. 11 and 12, but most of the | + | Opus 10 appeared as Le Cène print No. 544 in 1729, in rough coincidence with Vivaldi's violin concertos Opp. 11 and 12, but most of the works are likely to have been composed years earlier. All three volumes were published in Amsterdam. Although each published set was designed for a market oriented towards a standardized, relatively neutral instrumentation, the origins and histories of individual works were varied. The indications suggested by the related concertos listed on the lower half of the chart do not include subtle differences of instrumental alternatives and/or pairings--for example, an independent oboe part vs. an oboe part duplicating a second violin, a separate cello part vs. an unspecified basso, and so forth. These are among the kinds of details that have necessitated separate catalog listings for works that are musically similar. One manuscript source for No. 3 is scored for recorder rather than violin. |

The transverse flute and the recorder were both associated with a certain freedom of timbral choice. The so-called chamber concertos (RV 570, 90, and 101) for flute (or recorder), oboe, bassoon, violin, and bass can be understood to signify this sense of free play, rather than to represent a sub-genre cast in concrete. Although Vivaldi's chamber concertos had few analogues during Vivaldi's lifetime, they paved the way to a rich chamber repertory in the later eighteenth century. | The transverse flute and the recorder were both associated with a certain freedom of timbral choice. The so-called chamber concertos (RV 570, 90, and 101) for flute (or recorder), oboe, bassoon, violin, and bass can be understood to signify this sense of free play, rather than to represent a sub-genre cast in concrete. Although Vivaldi's chamber concertos had few analogues during Vivaldi's lifetime, they paved the way to a rich chamber repertory in the later eighteenth century. | ||

| Line 312: | Line 222: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| − | The first three works are the best known ones of the collection, but | + | The first three works are the best known ones of the collection. Their nicknames gave them easy recognition, but the nicknames accrued over time. Their programmatic allusions are largely confirmed in associated manuscripts. Storms at sea and phantoms of the night (the images cultivated by the first two pieces) were staples of opera staging at Venice's Teatro Sant'Angelo, the Venetian theater with which Vivaldi and his father were most consistently associated. Both played a prominent role in Venetian scene paintings contemporary with Vivaldi. |

| − | The representation of sleep in the fourth movement of Op 10, No. 2, is illustrative of a fascination with dreams and the supernatural that was probed cautiously on the stage because of the pervasive scrutiny of religious censors. However, the dramatization of darkness fed Sant'Angelo's penchant for grottoes and grotesque scenes. It is darkness that the bassoon invokes in the manuscript RV 501 (the loose analogue of No. 2), where | + | The representation of sleep in the fourth movement of Op 10, No. 2, is illustrative of a fascination with dreams and the supernatural that was probed cautiously on the stage because of the pervasive scrutiny of religious censors. However, the dramatization of darkness fed Sant'Angelo's penchant for grottoes and grotesque scenes. It is darkness that the bassoon invokes in the manuscript RV 501 (the loose analogue of No. 2), where the key is Bb Major rather than G Minor. |

| − | Vivaldi's depictions of bird-calls (in Op. 10, No. 3 a bullfinch) were prevalent not only in his concertos but also in his operas, and in dozens of works by other composers of the time. | + | Vivaldi's depictions of bird-calls (in Op. 10, No. 3 a bullfinch) were prevalent not only in his concertos but also in his operas, and in dozens of works by other composers of the time. Though elsewhere they often suggested the formal gardens that were so much promoted by the aristocracy, in Vivaldi's case they are more often a natural depiction of bucolic habitats consistent with the imagery of Arcadian shepherds than of programmed landscapes abroad. |

| − | The <i>sopranino</i> recorder concerto RV 444 is a unique work among Vivaldi's <i>oeuvre</i>, although it could easily have been adapted to a different soloist. It would have suited a virtuoso of considerable renown. | + | The <i>sopranino</i> recorder concerto RV 444 is a unique work among Vivaldi's <i>oeuvre</i>, although it could easily have been adapted to a different soloist. It would have best suited a virtuoso of considerable renown. |

The parts provided here correspond to the Dover Publication entitled <i>Six Concertos for Flute and String Orchestra, Op. 10, and Related Variants</i>. | The parts provided here correspond to the Dover Publication entitled <i>Six Concertos for Flute and String Orchestra, Op. 10, and Related Variants</i>. | ||

| − | ===Op. 11: <i>Sei concerti</i>=== | + | ===Op. 11: <i>Sei concerti a violino principale</i>=== |

| − | In Opp. 11 and 12 Vivaldi returned to the practice of publishing six works at a time. His earlier 12-work prints are usually presented as two books of six, but there were practical benefits to grouping the works into two sets. | + | In Opp. 11 and 12 Vivaldi returned to the practice of publishing six works at a time. His earlier 12-work prints are usually presented as two books of six, but there were practical benefits to grouping the works into two sets. Opp. 11 and 12 appear to be cut from the same cloth and may have been intended initially as a single publication. Their Amsterdam print numbers from presses of Michel Charles Le Cène (1729) were 545 and 546. In comparison to all of Vivaldi's music printed since 1711 they were poorly circulated. Some uncertainty hovers over the question of whether Vivaldi authorized these prints. He explicitly avoided publication of sets after the publication of Op. 12, preferring instead to sell pieces singly to well-heeled fans and amateurs. |

| + | |||

| + | Many solo passages are a challenge to the principal violinist. Vivaldi's full catalog of virtuoso techniques--double, triple, and quadruple stops, bariolage and a host of other difficult manners of passagework lurk within them. Several of the works are well known today. Op. 11, No. 5 was especially popular. Vivaldi's autograph appeared as No. 3 in the set of twelve concertos he presented to the emperor Charles VI during a visit to Trieste (1728). Miscellaneous parts in the Austrian National Library MS 15996 omit the music for first violin. | ||

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

| Line 329: | Line 241: | ||

! Opus, Work No. !! Ryom number !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Related works !! Score | ! Opus, Work No. !! Ryom number !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Related works !! Score | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 11, No. 1 || RV 207 || Concerto / VPr | + | | Op. 11, No. 1 || RV 207 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || D Major || <small>The three known manuscript sources are in Turin, Dresden (partly copied by Joh. Georg Pisendel, Dresden's <i>Kapellmeister</i>), and Venice, where the conservatory title is dedicated to one of Vivaldi's most accomplished students, Anna Maria of the Pietà</small>. || [https://pdf.musedata.org/?id=vivaldi-op11-no1 score] |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 11, No. 2 || RV 277 || Concerto / VPr | + | | Op. 11, No. 2 || RV 277 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || E Minor || <small>Nicknamed "Il Favorito". Appears as No. 11 of <i>La Cetra</i>, the concerto collection Vivaldi dedicated to the emperor Charles VI (1728).</small> || [https://pdf.musedata.org/?id=vivaldi-op11-no2 score] |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 11, No. 3 || RV 336 || Concerto / VPr | + | | Op. 11, No. 3 || RV 336 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || A Major || <small>May be from the early 1720s.</small>|| [https://pdf.musedata.org/?id=vivaldi-op11-no3 score] |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 11, No. 4 || RV 308 || Concerto / VPr | + | | Op. 11, No. 4 || RV 308 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || G Major || <small>Another concerto dedicated to Anna Maria of the Pietà.</small> || [https://pdf.musedata.org/?id=vivaldi-op11-no4 score] |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 11, No. 5 || RV 202 || Concerto / VPr | + | | Op. 11, No. 5 || RV 202 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || G Minor || <small>Material added here is partly in Pisendel's hand.</small> || [https://pdf.musedata.org/?id=vivaldi-op11-no5 score] |

| + | <small>[http://digital.slub-dresden.de/id340096659 Manuscript, Dresden SLUB 2389-O-122</small>] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 11, No. 6 || RV 260 || Concerto / VPr | + | | Op. 11, No. 6 || RV 260 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org || C Minor || <small>Preserved in Dresden and Venice (in the latter case with dedication to Anna Maria of the Pietà). May be from the early 1720s. See also Op. 9, No. 3 (RV 334); RV 460 for Ob; V1 V2 Va Vc Org</small> || [https://pdf.musedata.org/?id=vivaldi-op11-no6 score] |

|} | |} | ||

| − | ===Op. 12: <i>Sei concerti</i>=== | + | ===Op. 12: <i>Sei concerti a violino principale</i>=== |

| − | Vivaldi six concertos Op. 12 (1729) represent the final printed publication of his music. | + | Vivaldi's six concertos Op. 12 (1729) represent the final printed publication of his music. Like op. 11, op. 12 includes works (e.g. nos. 1, 2, 6) that lack inclusion in any other source, print or manuscript. This allows that the publication as a whole was not authorized by the composer. It also invited questions of attribution. The authorship of two other works (nos. 3 and 5) is confirmed by the presence of analogous pieces in the Giordano manuscript series in Turin. The gem of the collection is no. 4, with its brisk motifs and multiple stops, features not readily present in the other five concertos. Yet the brilliant final movement is unmistakably Vivaldi's. |

{| class="wikitable sortable" | {| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

| Line 349: | Line 262: | ||

! Opus, Work No. !! Ryom number !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Score | ! Opus, Work No. !! Ryom number !! Genre / Instrumentation !! Key !! Score | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 12, No. 1 || RV 317 || Concerto / VPr V1 V2 Va Vc | + | | Op. 12, No. 1 || RV 317 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Bc || G Minor || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 12, No. 2 || RV 244 || Concerto / VPr V1 V2 Va Vc | + | | Op. 12, No. 2 || RV 244 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Bc || D Minor || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 12, No. 3 || RV 124 || Concerto / VPr V1 V2 Va Vc | + | | Op. 12, No. 3 || RV 124 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Bc || D Major || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 12, No. 4 || RV 173 || Concerto / VPr V1 V2 Va Vc | + | | Op. 12, No. 4 || RV 173 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Bc || C Major || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 12, No. 5 || RV 379 || Concerto / VPr V1 V2 Va Vc | + | | Op. 12, No. 5 || RV 379 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Bc || B{{music|flat}} Major || Example |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Op. 12, No. 6 || RV 361 || Concerto / VPr V1 V2 Va Vc | + | | Op. 12, No. 6 || RV 361 || Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Bc || B{{music|flat}} Major || Example |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 366: | Line 279: | ||

The number of Vivaldi's unpublished instrumental pieces greatly exceeds those that were printed in the composer's lifetime. They generally follow the same lines and populate the same genres of sonata and concerto. The two most conspicuous differences between the published and unpublished works are that dates of composition are more difficult to pin down for the manuscript works and nearly all of the works with obbligato wind parts were never published. | The number of Vivaldi's unpublished instrumental pieces greatly exceeds those that were printed in the composer's lifetime. They generally follow the same lines and populate the same genres of sonata and concerto. The two most conspicuous differences between the published and unpublished works are that dates of composition are more difficult to pin down for the manuscript works and nearly all of the works with obbligato wind parts were never published. | ||

| − | Why were works with obbligato winds not published in Vivaldi's time? The demand for works with wind parts was much lower, while learning to play the violin was a popular activity among noblemen. Numerous accounts of special occasions note the addition of local amateur players to orchestras for serenatas and sinfonias. Learning to play a bowed instrument conferred a certain prestige on the fledgling performer. | + | Why were works with obbligato winds not published in Vivaldi's time? The demand for works with wind parts was much lower, while learning to play the violin was a popular activity among noblemen. Numerous accounts of special occasions note the addition of local amateur players to orchestras for serenatas and sinfonias. Learning to play a bowed instrument conferred a certain prestige on the fledgling performer. Many wind parts were added to copyists to suit local resources. |

| − | In Italy wind instruments, which were not readily available, were required in music for particular kinds of ceremonies or scenes in operas. | + | In Italy wind instruments, which were not readily available, were required in music for particular kinds of ceremonies or scenes in operas. Nasal reeds, such as the oboe, were used in funeral music or to signify impending doom. Recorders and cross-flutes were associated with peasants and with dancing. Bassoons could signify the underworld. Among brasses, trumpets had been used discreetly to represent military advances and triumphs since before Vivaldi was born, but their appearances were few. |

| − | Vivaldi's interactions with musicians from north of the Alps provided him with incentives to score parts for oboes, bassoons, recorders, cross-flutes, and other novel instruments. He also adapted some of his concertos | + | Vivaldi's interactions with musicians from north of the Alps provided him with incentives to score parts for oboes, bassoons, recorders, cross-flutes, and other novel instruments. He also adapted some of his concertos to feature a wind instrument (usually an oboe) in lieu of a principal violin. Op. 10 is the only print that shows off his wind interests here, but the menu of works related to that set of six (grouped here with Op. 10) shows the latitude (or lack thereof) in adaptations. |

| − | Yet in Italy the idea of using these different timbres together with strings was one that remained somewhat foreign at the end of Vivaldi's life. In his operas, winds were usually deployed in pairs. Quite often their use was limited to opening performances, when entrance fees were higher. Because their players were paid one night at a time, the wind parts did not always survive. Modern editions represent optimal versions of the work at hand, but the fact that many wind parts have only one or two solo episodes in an entire work and otherwise double string parts allows for some latitude in interpretation and some accommodation of strained circumstances. | + | Yet in Italy, the idea of using these different timbres together with strings was one that remained somewhat foreign at the end of Vivaldi's life. In his operas, winds were usually deployed in pairs. Quite often their use was limited to opening performances, when entrance fees were higher. Because their players were paid one night at a time, the wind parts did not always survive. Modern editions represent optimal versions of the work at hand, but the fact that many wind parts have only one or two solo episodes in an entire work and otherwise double string parts allows for some latitude in interpretation and some accommodation of strained circumstances. |

=Oratorios= | =Oratorios= | ||

| − | == | + | == <i>Juditha triumphans</i> == |

| + | |||

| + | See the dedicated page for Vivaldi's oratorio, [[Juditha triumphans]]. | ||

| − | + | = References = | |

Latest revision as of 18:22, 2 May 2024

Contents

- 1 Published Sonatas and Concertos

- 1.1 Op. 1: Suonate da camera a trè, due violini e violone o cembalo

- 1.2 Op. 2: Sonate a violino e basso per il cembalo

- 1.3 Op. 3: L'estro armonico: Concerti

- 1.4 Op. 4: La Stravaganza: Concerti in six parts

- 1.5 Op. 5: VI Sonate/quattro à violino solo e basso e due a due violini e basso continuo

- 1.6 Op. 6: VI Concerti à cinque strumenti: 3 violini, alto viola, e basso continuo

- 1.7 Op. 7: Concerti a 5 strumenti: Tre violini, alto viola e basso continuo

- 1.8 Op. 8: Il cimento dell'armonia e dell'invenzione: Concerti a quattro e cinque

- 1.9 Op. 9: La cetra. Concerti

- 1.10 Op. 10: VI Concerti a flauto traverso

- 1.11 Op. 11: Sei concerti a violino principale

- 1.12 Op. 12: Sei concerti a violino principale

- 2 Unpublished instrumental works

- 3 Oratorios

- 4 References

Published Sonatas and Concertos

Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (1678-1741) is best known to modern audiences for his instrumental music. Like most composers of his time, Vivaldi composed in the formal medium of the sonata in his earliest publications (from 1703). His reputation was propelled by his concertos, the earliest of which appeared in 1711. This is still the genre with which he is most widely associated.

Op. 1: Suonate da camera a trè, due violini e violone o cembalo

Vivaldi's twelve sonatas Op. 1 are presumed to have been published prior to his appointment as maestro di violino at the Ospedale della Pietà, Venice, because he is described without reference to the institution as "musico di violino, professore veneto" (a violinist and teacher in the Veneto). The works were dedicated to the count Annibale Gambara, one of five sons in a big family of noblemen from Brescia (the city in which Vivaldi's father was born), a provincial capital in the western Veneto. The Gambara had a modest palace on the Grand Canal in the Venetian parish of San Barnabà.

These trio sonatas contained various numbers of movements (3 to 6), most in binary form. The four outer works (Nos. 1, 2, 11, and 12) are in minor keys, the others in major ones. The best known work is Op. 1, No. 12, an ambitious set of variations on the folìa. Vivaldi may have been inspired by Arcangelo Corelli's set of Folìa variations Op. 5, No. 12 (1700), but the trio texture changes the dynamics of the realization substantially.

The earliest surviving print of Op. 1 was published in Venice (G. Sala) in 1705. Only fragments of it survive today in the library of the "Benedetto Marcello" Conservatory in Venice. (Scholars suspect that the music predated Vivaldi's appointment at the Ospedale of the Pietà, it is not mentioned in the title-page of Op. 1.) Vivaldi's collection was reprinted in Amsterdam in 1723 (E. Roger, as print No. 363), in Paris in 1759 (Le Clerc), and in Austria in 1759. Many movements are brief and musically simple, so much so that were one to judge from this opus alone, one would not have anticipated the kind of success that Vivaldi later found. Critical notes for Vivaldi's Op. 1.

| Opus | Ryom No. | Genre / Instrumentation | Key | VHV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/1 | RV 73 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | G Minor | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 1/2 | RV 67 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | E Minor | 1/2 | 1/2 |

| 1/3 | RV 61 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | C Major | 1/3 | 1/3 |

| 1/4 | RV 66 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | E Major | 1/4 | 1/4 |

| 1/5 | RV 69 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | F Major | 1/5 | 1/5 |

| 1/6 | RV 62 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | D Major | 1/6 | 1/6 |

| 1/7 | RV 65 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | E♭ Major | 1/7 | 1/7 |

| 1/8 | RV 64 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | D Major | 1/8 | 1/8 |

| 1/9 | RV 75 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | A Major | 1/9 | 1/9 |

| 1/10 | RV 78 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | B♭ Major | 1/10 | 1/10 |

| 1/11 | RV 79 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | B Minor | 1/11 | 1/11 |

| 1/12 | RV 63 | Sonata / Vn1 Vn2 Vne (alt. cem) | D Minor | 1/12 | 1/12 |

Op. 2: Sonate a violino e basso per il cembalo

The trio sonata, over which Vivaldi had exhibited his command in Op. 1, had been the most prevalent instrumental genre of the 1690s, but in the first decade of the eighteenth century interest began to gravitate towards the "solo" sonata--a work in several movements for one ensemble instrument and a basso continuo. In this 1709 collection by the Venetian publisher Antonio Bortoli, Vivaldi pursued a more expressive vein of musical enticement. The opus was dedicated to the visiting young monarch Frederick IV of Denmark. As prince of Schleswig-Holstein, his extended stay drew much artistic attention. No fewer than three operas were dedicated to him.

Seven of these sonatas were cast in minor keys. (An asterisk (*) indicates a transcription using the key signature of the original print, while ** indicates a modernized key signature.) The movement structure of these early prints remained variable. Vivaldi was moving in the direction of fewer movements but in coincidence we find greater musical elaboration within longer movement. The composer was now described as a maestro dei concerti (concertmaster) of the Ospedale della Pietà.

| Opus/Work No. | Ryom No. | Genre / Inst. | Key | VHV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2/1 | RV 27 | Sonata / Vn Cem | G Minor | 2/1*; 2/1a** | 2/1 |

| 2/2 | RV 31 | Sonata / Vn Cem | A Major | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| 2/3 | RV 14 | Sonata / Vn Cem | D Minor | 2/3 | 2/3 |

| 2/4 | RV 20 | Sonata / Vn Cem | F Major | 2/4 | 2/4 |

| 2/5 | RV 36 | Sonata / Vn Cem | B Minor | 2/5 | 2/5 |

| 2/6 | RV 1 | Sonata / Vn Cem | C Major | 2/6 | 2/6 |

| 2/7 | RV 8 | Sonata / Vn Cem | C Minor | 2/7*; 2/7a** | 2/7 |

| 2/8 | RV 23 | Sonata / Vn Cem | G Major | 2/8 | 2/8 |

| 2/9 | RV 16 | Sonata / Vn Cem | E Minor | 2/9 | 2/9 |

| 2/10 | RV 21 | Sonata / Vn Cem | F Minor | 2/10 | 2/10 |

| 2/11 | RV 9 | Sonata / Vn Cem | D Major | 2/11 | 2/11 |

| 2/12 | RV 32 | Sonata / Vn Cem | A Minor | 2/12 | 2/12 |

Like Op. 1, Op. 2 had a long afterlife in both reprints and manuscript copies, mainly abroad. These included the publications of E. Roger (Amsterdam, 1712) and several editions (1721-1730) by I. Walsh and J. Young (London). [Critical notes for Vivaldi's Op. 2.]

Op. 3: L'estro armonico: Concerti

The first concertos by Vivaldi to reach print were those of Opus 3 (Amsterdam, 1711). With them Vivaldi suddenly became a celebrity, for although he was well known as a virtuoso, his previously published works had found a relatively modest reception. Vivaldi's titles remained as they were in Op. 2. Most composers described the contents of a publication in sufficient detail to indicate instrumentation, but Vivaldi settled for the word "Concerti" in order to allow space for the titles of his patron, the Grand Prince of Tuscany, Ferdinando III (1663-1713). The Grand Prince, who led a flamboyant life, enjoyed his visits to Venice, where however he contracted syphilis in 1696. This led to his premature death and changed the course of Tuscan (and imperial) history. Meanwhile, however, his patronage of music benefited many composers of the time including Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1751), George Frideric Handel (1685-1759), and Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725). His Bavarian wife, Violante Beatrice (1673-1731), was in many ways a still more significant supporter of individual singers and instrumentalists.

Having now completed eight years of teaching at the Ospedale of the Pietà in Venice, Vivaldi shows himself to have experimented with a variety of approaches to textures and groupings of instruments. These twelve works are arranged cyclically, such that Nos. 1, 4, 7, and 10 are scored for four violins and string orchestra; Nos. 2, 5, 8, and 11 for two violins, violoncello, and string orchestra; and Nos. 3, 6, 9, and 12 for solo violin (Violino Principale) and string orchestra. Within the concertino groups (four violins or, alternatively, two violins and violoncello), there is further separation. The "four violins" model often involves the pairing of the instruments such that one duo imitates another. This kind of experimentation is suggested by the word estro, which refers to gestational properties whereby one musical passage generates the need for the next. In musical terms, the sophistication of the idea represented an enormous step forward for Vivaldi, whose first sonatas were primitive and somewhat generic by comparison.

Additionally, the music was more cogent than before, the organization manifestly rational. The imaginative scoring, careful markup, and newly pungent musical effects were novelties not found in Opp. 1 or 2. If he had leaned on the familiar models of Arcangelo Corelli (1753-1713) before, Vivaldi was now producing music that was novel, ambitious, and aesthetically pleasing. Largely in coincidence with this publication, Vivaldi's concerts at the Pietà began to win plaudits from a succession of visiting dignitaries from abroad.

Within the context of the early concerto, Op. 3 was equally noteworthy. The now elderly Corelli had perfected the concerto grosso [his Op. 6 would be published only posthumously in 1714]. Vivaldi's concertos for two and four violins had some debts to these works, but his concertos for solo violin and orchestra did not have Corellian models to follow. The trumpet concertos by Giuseppe Torelli (1658-1709) are an oft mentioned alternative model, but Vivaldi's skills at articulation and exhibitionism were unrivaled. The violin was capable of much greater subtlety than the trumpet.

Dissemination of Individual Works from Op. 3

The Concerti Op. 3 were so popular that the entire opus was reprinted in Amsterdam within a year. Other reprints followed in both London and Paris through 1751. Because of the cyclical rotation of different combinations of instruments from work to work, individual pieces in Op. 3 led themselves to diverse uses. The basic organization is shown in the table. Parsed one way, it is a four-fold cycle of three works. The textures vary with the instrumentation.

Several works from Opus 3 took on lives of their own. Six works (indicated by an asterisk*) were transcribed by J. S. Bach, and there are faint clues that Bach may have transcribed them all. Bach was highly sensitive to the cyclical instrumentation of Vivaldi's collection: Nos 1, 4, 7, and 10 were set for two pairs of solo violins; Nos. 2, 5, 8, and 11 for a trio of soloists (two violins and violoncello); Nos. 3, 6, 9, and 12 for principal violin, in all cases with string orchestra. As the table below shows, Bach chose the second type for an organ adaptation and the third type for concertos for harpsichord and strings, while the first type served as a model for his lone concerto for four harpsichords and strings. The trio sonata, which was at its peak in the years 1700-1710, was a popular reservoir for organ transcriptions in Germany, but the other adaptations had no such currency. Concertos for four harpsichords were unknown.

Wide circulation of Vivaldi's concertos was further stimulated by John Walsh's edition of Op. 3 in c. 1715. In this print, the order of Nos. 6-9 was altered so that these concertos became Nos. 8, 9, 6, and 7. The clavichord transcriptions of Anne Dawson include many works in Vivaldi's Opp. 3 and 4 and show a further dimension of the music's adaptation. Numerous transcriptions and copies survive in Europe and North America.

CCARH Scores and Parts for Opus 3

CCARH cooperated with Dover Publications Inc. in producing the scores that appear in L'estro armonico: Twelve Concertos for Violins and String Orchestra, Op. 3. The cover is shown below. The collection entitled L'estro armonico was the first title under Vivaldi's name to draw widespread attention. It is likely that some of the works had already been performed in selected gatherings. They were profusely copied, arranged, and reprinted (with numerous variants) over the next few decades. This edition is based primarily on the prints of Etienne Roger Nos. 50 (containing parts for Nos. 1-6) and 51 (Nos 7-12; 1711) in conjunction with several manuscript sources for specific works.

For bound paper copies, see Vivaldi, Antonio. "L'Estro armonico", Op. 3 in Full Score: 12 Concertos for Violins and String Orchestra, ed. Eleanor Selfridge-Field (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications; 1999). Available from Amazon ISBN 0-486-40631-8 and Dover ISBN 0-486-40631-8.

| Opus, Work No. | Ryom No. | Genre / Instrumentation | Key | PDF parts (CCARH/Dover edn.) | Related pieces and transcriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Op. 3, No. 1 | RV 549 | Concerto / VVVV; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | D Major | [1] | |

| Op. 3, No. 2 | RV 578 | Concerto / VVVc; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | G Minor | Example | |

| Op. 3, No. 3 | RV 310 | Concerto / V; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | G Major | Example | JS Bach: BWV 978 |

| Op. 3, No. 4 | RV 550 | Concerto / VVVV; V1,V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | E Minor | Example | |

| Op. 3, No. 5 | RV 519* | Concerto / VVVc; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | A Major | Example | Dawson transcription |

| Op. 3, No. 6 | RV 356 | Concerto / V; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | A Minor | Example | |

| Op. 3, No. 7 | RV 567 | Concerto / VVVV; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | F Major | Example | Dawson transcription |

| Op. 3, No. 8 | RV 522 | Concerto / VVVc; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | A Minor | Example | JS Bach: BWV 593 (Organ with two manuals and a pedalboard) |

| Op. 3, No. 9 | RV 230* | Concerto / V; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | D Major | Example | JS Bach: BWV 972, Dawson transcription |

| Op. 3, No. 10 | RV 580 | Concerto / VVVV; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | B Minor | Example | JS Bach: BWV 1065 (VVVV, Strings) |

| Op. 3, No. 11 | RV 565 | Concerto / VVVc; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | D Minor | Example | JS/WF Bach: BWV 596 (organ as above). String version (BWV 596/3) by Wilhelm Friedemann Bach. Fugal subject from Benedetto Marcello, Op. 1, No. 2 (1708) |

| Op. 3, No. 12 | RV 265 | Concerto / V; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Vne, Cem | C Major | Example | JS Bach BWV 976; Dawson transcription |

The Dawson transcriptions for Nos. 5, 7, 8, and 12 as a group are available here.

Op. 4: La Stravaganza: Concerti in six parts

Vivaldi's violin concertos Op. 4 (announced in London on January 1, 1715) achieved a much broader penetration of the European market than any previous publication of his music. The collection, published in Amsterdam as Estienne Roger's prints Nos. 399 and 400, bore the title La Stravaganza (The Extravaganza), a designation popular at the time. In musical contexts it usually referred to chromatic harmonies, but in Vivaldi's case it forewarned prospective players of the challenges posed, especially for the principal violinist. (Up to this time, Roger had principally offered trio sonatas and concerti grossi, which were less demanding.)

Op. 4 was a compendium of virtuoso techniques that were popularized by Vivaldi, who, as a performer, was known far and wide for his daring. His near-peers in this regard were violinist-composers such as Tomaso Albinoni and Lodovico Madonis, but their most demanding works appeared some years later and were less widely distributed. Op. 4 was dedicated to a Venetian nobleman, Vettor Delfin, whose family were largely engaged in military affairs. With only one exception (Op. 4, No. 7), the concertos were written in three movements.

At the time Op. 4 appeared, Vivaldi had been filling holes left by the departure of Francesco Gasparini (1661-1727) at the Pietà. He was now turning his attention to motets and oratorios per force to bridge the gap left by Gasparini. It is therefore likely that most of these pieces were composed before the elder maestro's departure. Reprints of Op. 4 appeared in 1723, 1728, and 1730, but selected individual works enjoyed independent circulation. Vivaldi had now reached the point where demand for his instrumental music exceeded the amount of time he could afford to devote to them. It may be for this reason that echoes of Op. 4 appear in a few later works by Vivaldi. Op. 7, No. 1, for example, was a first cousin of Op. 4, No. 9; myriad other variants of this set were quoted in later works. The cumulative effect was a splintering of work-identities that still confuses musicians today. Vivaldi himself adapted many of his works to suit new purposes as appropriate occasions arose. Critical notes for Op. 4.

| Opus, Work No. | Ryom No. | Genre / Instrumentation | Key | Related works | Transcriptions by others | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Op. 4, No. 1 | RV 383a | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | B♭ Major | RV 381, RV 383 | RV 383a | JS Bach: BWV 980, Dawson MS, ff. 14v-18r | |

| Op. 4, No. 2 | RV 279 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, VC, Org | E Minor | RV 279 | |||

| Op. 4, No. 3 | RV 301 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | G Major | RV 301 | |||

| Op. 4, No. 4 | RV 357 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | A Minor | RV 357 | |||

| Op. 4, No. 5 | RV 347 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | A Major | RV 347 | |||

| Op. 4, No. 6 | RV 316a | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | G Minor | RV 316 | RV 316a | JS Bach: BWV 975, Dawson MS, ff. 6v-10v | |

| Op. 4, No. 7 | RV 185 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | C Major | RV 185 | |||

| Op. 4, No. 8 | RV 249 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | D Minor | RV 249 | |||

| Op. 4, No. 9 | RV 284 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | F Major | RV 285, RV 285a | RV 284 | ||

| Op. 4, No. 10 | RV 196 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | C Minor | RV 196 | Dawson MS, ff. 22r-25r | ||

| Op. 4, No. 11 | RV 204 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | D Major | RV 204 | Dawson MS, ff. 65r-68r | ||

| Op. 4, No. 12 | RV 298 | Concerto / VPr; V1, V2, Va, Vc, Org | G Major | RV 291, RV 357 | RV 298 |

Op. 5: VI Sonate/quattro à violino solo e basso e due a due violini e basso continuo

Four of the six sonatas of Op. 5, published in Amsterdam (1716) as Jeanne Roger's print No. 418, were remainders of Vivaldi's Op. 2, an opus consisting of a dozen solo violin sonatas. These works appeared with the added information O vero Parte Seconda del Opera Seconda". During the visit of the young Danish king Frederick Christian IV to Venice in the winter of 1709, a great many banquets and balls were planned. Easily half of them were canceled either by hosts or guests because many people (including the doge and one of the Venetian Republic's official hosts) died. No autograph material for this opus survives. Op. 2 had been dedicated to Frederick Christian, but Op. 5, containing a mixed repertory, was an orphan of sorts. It lacked a dedicatee, although an edition by M.C. Le Cène was brought out in c1723. Although few works were copied in manuscript, an exception was the first movement of Op. 5, No. 6, which was included in J. B. Cartier's L'Art du Violon (Paris, 1798).

| Opus, Work No. | Ryom No. | Genre / Instrumentation | Key | Score (Roger) | Score (Le Cène) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Op. 5, No. 1 [Op. 2, No. 13] | RV 18 | Sonata / V, Bc | F Major | Example | Example |

| Op. 5, No. 2 [Op. 2, No. 14] | RV 30 | Sonata / V, Bc | A Major | Example | Example |

| Op. 5, No. 3 [Op. 2, No. 15] | RV 33 | Sonata / V, Bc | B♭ Major | Example | Example |

| Op. 5, No. 4 [Op. 2, No. 16] | RV 35 | Sonata / V, Bc | B Minor | Example | Example |

| Op. 5, No. 5 [Op. 2, No. 17] | RV 76 | Sonata / V1, V2, Bc | B♭ Major | Example | Example |

| Op. 5, No. 6 [Op. 2, No. 18] | RV 72 | Sonata / V1, V2, Bc | G Minor | Example | Example |

Critical comments: Despite its thin trail of copies and imitations, the opus is presented in slightly different ways by Jeanne Roger and M.C. Le Cène, although both employ the print number 418. Roger is generous with bowing marks, which bring a certain grace to the music. Yet the Roger lacks continuo figuration, which Le Cène provides generously. These differences in presentation suggest a difference in intended modes of performance--the Roger assuming the use of violin and string bass only, while the Le Cène aims for a keyboard continuo, probably with string bass reinforcement. Le Cène give movement tempo designations (Largo, Allegro, Presto) but excludes the dynamics indications found in Roger. Roger may have allowed for notes inégales in Op. 5, No. 1, for although the dotted patterns are given equivalently in Le Cène, the double dot in the final bar of the Preludio of Roger is an ordinary dot in Le Cène. Detailed notes on individual works in both prints

Op. 6: VI Concerti à cinque strumenti: 3 violini, alto viola, e basso continuo

The six concertos for violin and strings of Op. 6, published in Amsterdam in 1716-1717 by Jeanne Roger (as her firm's print No. 452) represent both a continuation and a departure. The instrumental requirements are identical to those of Op. 4: they require a principal violin and a small string orchestra. This short collection could have served as a supplement to Op. 4, given the pattern set by Opp. 2 and 5 (another short set). The absence of a dedicatee and sundry details of the music suggest that Vivaldi did not actively seek this publication and that the print was therefore unauthorized. Mme. Roger heralded Vivaldi's titles as maestro di violino and maestro di concerti at the Pietà.

Musically, four of the six works are in minor keys. Again forming a parallel with Op. 5, it was not followed by myriad other editions, although Le Cène issued one (undated) reprint.

| Opus, Work No. | Ryom No. | Genre / Instrumentation | Key | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Op. 6, No. 1 | RV 324 | Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org | G Minor | Example |

| Op. 6, No. 2 | RV 259 | Converto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org | C Minor | Example |

| Op. 6, No. 3 | RV 318 | Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org | G Minor | Example |

| Op. 6, No. 4 | RV 216 | Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org | D Major | Example |

| Op. 6, No. 5 | RV 280 | Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org | E Minor | Example |

| Op. 6, No. 6 | RV 239 | Concerto / VPr; V1 V2 Va Vc Org | D Minor | Example |

Op. 7: Concerti a 5 strumenti: Tre violini, alto viola e basso continuo